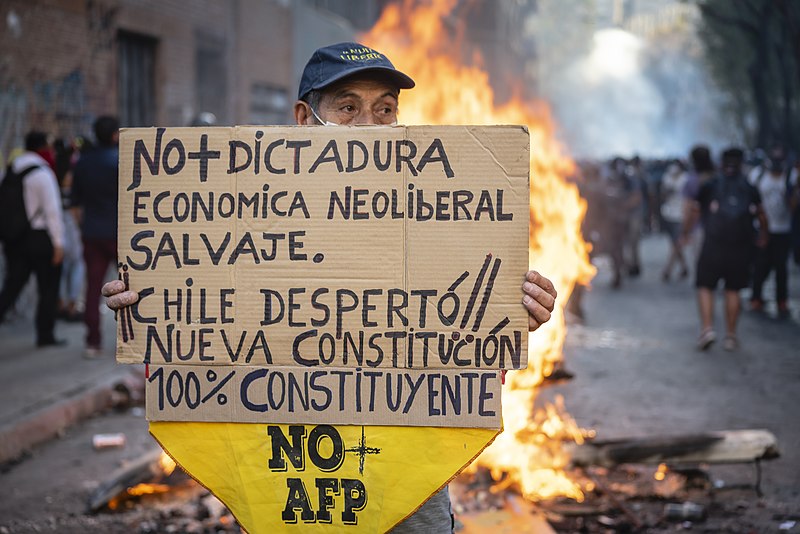

Why did the convention fail to win support for the new constitution when a solid majority voted for a new constitution?

There are many analyses going around. Some talk of a “silent majority”, others blame fake news, others talk about an image problem of the convention. Personally, I think that by trying to change everything, the convention failed to transmit a clear and believable message that the new constitution was going to deliver improved living standards for the vast majority.

The government has made many social promises, but has so far implemented little of them. The popularity of the centre-left president has fallen dramatically since the beginning of the year. Were the “no” votes also an expression of the deep frustration with the unfulfilled promises of the centre-left government?

Boric does not have a majority in Congress, so any reforms have to first be negotiated. The fact that all relevant social reforms imply government spending, means that the first reform to be implemented must be a tax reform. That is currently in parliament, and will be voted on in the next few weeks. The pension reform is soon to be sent to parliament, however 40 years of neoliberalism means that many people are wary of a pension system that deviates from the orthodoxy of individual savings. Most mistakenly believe that the reason for the poor pensions is due to theft on the part of the administrators, and not the lack of solidarity built into the system.

Another reason is that Boric slammed shut the door on pension fund withdrawals, despite his support for them during his time in opposition. This was an unpopular decision, however a necessary one given the disastrous side effects that these have brought.

What’s the idea behind pension fund withdrawals and why would they have had disastrous side effects?

The pension fund withdrawals came as a response to the lack of support financial from the Piñera administration during the pandemic, and also as a means of supposedly weakening the AFP private pension system. The withdrawals, and especially the political pressure for further withdrawals continued however after the quarantines had been lifted and the economy had begun to normalize.

The side effects came from two sides. Firstly, the release of a large amount of liquidity into the economy with constrained productive capacity further increases inflation, and secondly, liquidating a large amount of nationally held assets has reduced their prices, and pushed credit prices up substantially. Mortgage costs are 50% higher than 18 months ago, and in some places rents have doubled as a consequence of people not being able to buy apartments and being forced to rent.

Where was the support for the new constitution strongest?

In urban areas, in particular Valparaíso and the southern sectors of Santiago. Also notable that one of the 8 municipalities to vote in favour of the proposal was Ñuñoa, an upper middle class liberal municipality of Santiago.

And where was it weakest?

In the traditional upper class, and upper-middle class regions of Santiago, and in rural areas.

Is it possible to draw a conclusion about in which parts of the population the referendum was lost?

It appears as if was lost in poor and especially rural poor communities. There was no great sensation of working class people “voting for their side” in the urban areas, and in rural areas only 1 in 4 voted in favour of the proposal. It is true that the rich communities also rejected the proposal, but their numbers are irrelevant in a context of compulsory voting.

What was the public political process in the run-up to the referendum like?

Campaigning was much more subdued compared to the run-up to the presidential elections, however there were activities in most cities up and down the country. Supporters of the proposal held a half million strong rally in the centre of Santiago to mark the official end of the campaign, however this was not sufficient to change the result. There was very little technical discussion about the proposal itself, especially with the rejection campaign focusing on other issues such as crime and inflation to sow uncertainty in the minds of voters.

Who organised support for it?

The left wing parties and social movements.

About how many organisations are we talking?

The political fabric in Chile is fragmented. There would have been close to a dozen political parties supporting the proposal, although the Christian Democrats (centrist) were split down the middle. It is hard to put a number on the social movements as such.

Who organised the critics?

Right wing parties and spinoffs from some centre-left parties. Also, the large business organizations.

How much money went into each campaign?

The rejection side was funded at a far higher level than the approval side, although I am not sure on the exact figures.

How did the supporters of the new constitution react?

Mostly with sadness and disbelief. It is still not understood why the result was so poor for the approval vote.

Some German media explained that Chile is a traditionally conservative country. Do you think that can explain the result?

More than conservatism, I would say that a complete lack of trust in the political system is more at fault here. Given a long history of broken promises, it is not hard to sow doubts in voters’ minds about some eventual conspiracy to expropriate poor people’s houses, or for the proposed indigenous justice system to allow criminals to walk free.

Others argue that the government hasn‘t been able to contain the violence in the south. Can you briefly give an outline of the conflicts there?

The conflict has been going on for centuries however it has intensified over the past few years.

Could you please give a brief outline what it is about?

It is a classic situation of the indigenous Mapuche population seeking to restore their land which was taken from them by force in the second half of the 19th Century. An anti-colonial struggle to put it simply. The Araucanía is one of the few parts of America which was not subject to effective Spanish colonization, rather it was the newly independent Chilean state which finally defeated the Mapuche population.

Neither this government, nor the previous one has had any success in improving the situation in the south. There are however now indications that organised crime is infiltrating some of the militant groups in the south, further complicating matters.

How would organised crime benefit from infiltrating militant groups? Or militant groups getting involved with organized crime?

In much of the land which is being claimed by the militant groups, large scale industrial forestry operations are in place, and one of the chief crime activities is the theft of the timber – valued at almost $100 million USD per year. It is difficult to know what is really happening down there.

The indigenous Mapuche have been fighting against their oppression for decades. Has the Boric government really changed anything for the people?

In the 6 months since Boric took office, nothing of note has changed in the south.

Was President Gabriel Boric criticised for continuing military presence, state of emergency, and military the violence in the south even though he had a lot of support from indigenous groups during the elections?

He was criticized, however in practice he had no choice. It was either a state of emergency, or have the truck drivers shutting down the country, as they did during the summer holidays in February and again in March/April.

What’s the relation of the truck drivers to the conflict in Araucania?

Truck drivers, and especially the owners have a long history of (far) right agitation in Chile, dating back to 1972 when they accepted CIA money to shut down the country, paving the way for Pinochet. Being associated with the (far) right, they are also close the settler community in the South, who are one of the main targets of the militant groups. Truck drivers have also been target of attacks from militant groups, so they have gone on strike demanding more police presence on the highways. Due to its unique geography and lack of a modern rail system, Chile is especially vulnerable to truck strikes. With just 4 trucks parked across both directions of the main highway, Chile stops. There was also truck strike in the North earlier this year against Venezuelan refugees.

Will there be a new proposal now to fulfill the decision in favour of a new constitution?

I will believe it when I see it. It does appear however that there is a real change of tone from the right in favour of a new constitution.

Isn’t the current constitution exactly what the right wants?

The current constitution is what they want, but on the other hand, it is no longer politically viable to maintain it. The right (and everyone else) also needs stability, which the old constitution can no longer guarantee.

How does the government react to the result of the referendum?

There was a change of cabinet, however the right is pushing hard for a further weakening of their plans to introduce important changes in economic material. Unfortunately, the result has weakened their negotiating position substantially.

What is the reaction of the radical Left, the Unions and extra-parliamentary movements to that?

Mostly one of despair. I have not read anything of note from important union groups such as the Teachers’ Federation.

Have the roots of the uprising in 2019 been addressed by the new government?

No. The constitution, pensions, inequality etc are still all to be addressed. Not having a majority in parliament makes things more difficult, especially in the context of a global economic crisis with the local inflation at 14%.

The government in Chile is not the first left-wing government to dash hopes. What are the lessons?

I personally think they are doing all they can in what are very adverse conditions.

Chile is not the only country in Latin America where social upheaval led to a process for a new constitution. Venezuela and Bolivia are cases in point. However, these countries are also far from overcoming poverty, exploitation and oppression. What does that tell us about the prospects of channeling a social process involving millions into a constitutional process?

I am unfamiliar with the details of both of those processes unfortunately. In the case of Chile, the theme of the Constitution has been especially pertinent because it has been one of the cornerstones of the how the dictatorship has maintained a presence despite an appearance of democracy on the surface.

This article first appeared in German on the marx21 Website