This critique takes a radical postcolonial perspective, directly opposing the arguments made in the author’s book. Rather than providing a detailed analysis of the book’s content, this commentary aims to expose the underlying assumptions, distortions, and omissions that serve as key narrative strategies. We caution that readers seeking an in-depth examination of the book may not find this critique particularly useful; instead, it comments on the text as part of a broader attack on post-colonial scholars, showing that what is stated in those pages provides more information about the author and the intellectual climate in Germany than what is intended to be said about “others.”

Ingo Elbe’s Antisemitismus und postkoloniale Theorie was published in 2024, in the context of increasing global criticism of Israel’s policies and the ongoing genocide in Gaza. In Elbes’ 400-page book, he misrepresents reality by distorting facts and omitting critical aspects of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. This framing functions as an ideological defense, portraying postcolonial studies (PCS) as inherently anti-Semitic while deliberately overlooking Israel’s colonial occupation of Palestine.

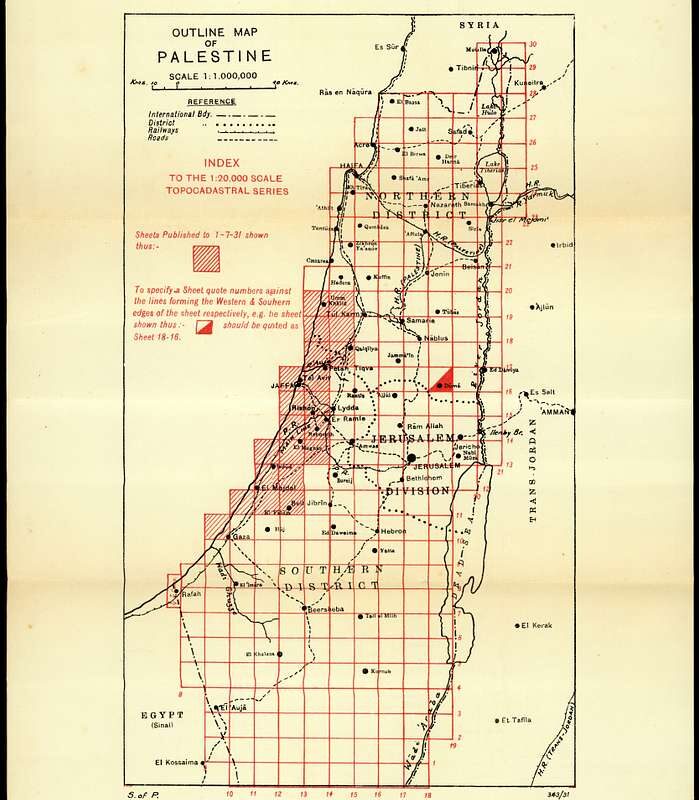

This narrative is a deliberate distortion based on a selective omission, portraying the conflict in the Middle East as primarily racial and religious. Yet, this intentional oversight seems to be a key tactic, a framing that obscures the real cause of the struggle, which is territorial and therefore settler-colonial. In this frame, the author ignores that Palestinians, as occupied people, have a right to resist their colonial occupation, a stance even supported by a United Nations resolution (1973). Within the flawed logic that conflates anti-Zionism with antisemitism, the attacks on postcolonial scholars appear justified, and undermining the reality of colonial occupation paves the way for the series of fallacious arguments that the book advances. Now, let us examine some of the book’s main points.

I. There is no colonialism

By selectively choosing facts, images, and arguments from various contexts and debates among postcolonial theorists—from Latin America to the U.S. to Asia and Africa—the author attempts to lend credibility to his central accusation. However, this strategy is both deliberate and deeply flawed. It is concerning to see the repeated use of a familiar rhetorical pattern, where any critique of Israel is swiftly dismissed as antisemitic. This tactic, often employed by those who defend Israel unconditionally, deflects legitimate criticism by either ignoring it or misrepresenting it as an attack motivated by deep “hate against Jews.”

Elbe presents his book as an intellectual contribution, but its focus on labeling postcolonial scholars and activists who critique Israel’s colonial practices as “antisemites” makes it resemble a defamation campaign. Although Elbe invokes the IHRA’s definition of antisemitism to justify his criticism, acknowledging but not accepting the much more nuanced definition provided by the Jerusalem declaration as the basis for defining “antisemitism.” So, conflating such criticism with anti-Jewish hatred, he sets the groundwork for his fallacious argument.

As Moshe Zuckermann argues in Antisemit!: Ein Vorwurf als Herrschaftsinstrument, the conflation of anti-Zionism with antisemitism is not only intellectually dishonest but also misrepresents the perspectives of Jewish voices critical of Israel. Figures like Zuckermann, Judith Butler, Naomi Klein, and Noam Chomsky have long emphasized that criticism of Israel’s policies is not the same as antisemitism, and all of them have been labelled as “Antisemitic” or “self-hating jews.”

Following the same narrative, widely used in Europe and Germany to defend and justify Israel’s actions, lies at the core of Elbe’s argumentative structure. This can be represented as a syllogism of a logical chain of denialism of Israel’s colonial nature:

- If Israel is not a colonial state, then it has not committed acts of apartheid or ethnic cleansing.

- Therefore, any accusation of genocide against Israel can be dismissed as anti-Semitic.

This argument unravels when confronted with overwhelming evidence of Israel’s settler-colonial history, as documented by historians like Ilan Pappe, Rashid Khalidi, and many others. Pappe’s work reveals the systematic expulsion and erasure of Palestinians, directly contradicting Elbe’s claim that such accusations are merely continuations of “anti-Jewish traditions.” It seems that Germans, who have the opportunity to redefine history, prefer to distance themselves from their historical antisemitism and project it onto critics of Israel, the left, and Arab communities, as if there had never been antisemitism in Germany. As the author Esra Özyürek recently said in an interview:

“This accusation goes back to the idea that you are allowed into the social contract as long as you prove that you have learned lessons from the Nazi regime. How do you prove it? By showing you are philosemitic, which in the German context means claiming allegiance to Israel. By definition, those who don’t do that don’t deserve to be part of Germany. The idea that Muslims have different cultural ideas, which makes them not fit into German culture, has been around for a long time. Now the focus is on antisemitism. There is this feeling among the Right and also the Left, settled around the idea that Muslims do not deserve to be here because they are anti-Semitic.”

For many of these so-called anti-anti-semites, to protest against a genocide wouls make you an antisemite. Even the claim “a genocide is happening” is called antisemitic propaganda. Elbe’s denial of Israel’s genocide reaches its extreme, extending accusations of antisemitism even to allegations brought forth by South Africa in the International Court of Justice (ICJ). The author writes, “The question arises whether the genocide accusation is not a continuation of the ritual murder and blood lie from the anti-Jewish tradition” (p. 25-26). Despite the “cautious,” question-like tone, the message of this sentence is clear: South Africa is commiting an antisemitic act by accusing Israel of genocide. This rhetorical tactic seeks to discredit criticism of Israel’s actions by framing them in a distorted historical narrative. In this strategy, denial and accusation work in tandem.

II. Against academic “mainstream”

Elbe positions himself as a defender of academia, claiming to challenge a “mainstream” supposedly dominated by PCS. However, the notion that he is battling an “academic hegemony” is far from reality in Germany and elsewhere, where PCS has been under relentless attack. As Allana Lentin notes in Why Race Still Matters, the narrative that PCS has taken over academia is often used by right-wing intellectuals to undermine critiques of Western imperialism. Other titles in the tradition of “clashing of civilizations“ discuss the distrust of the West, describing it as “war against the West” or even as hatred towards the West. Moreover, Elbe’s self-victimization can be read as part of a larger ideological strategy, aligning his work with the defense of the Western historical legacy.

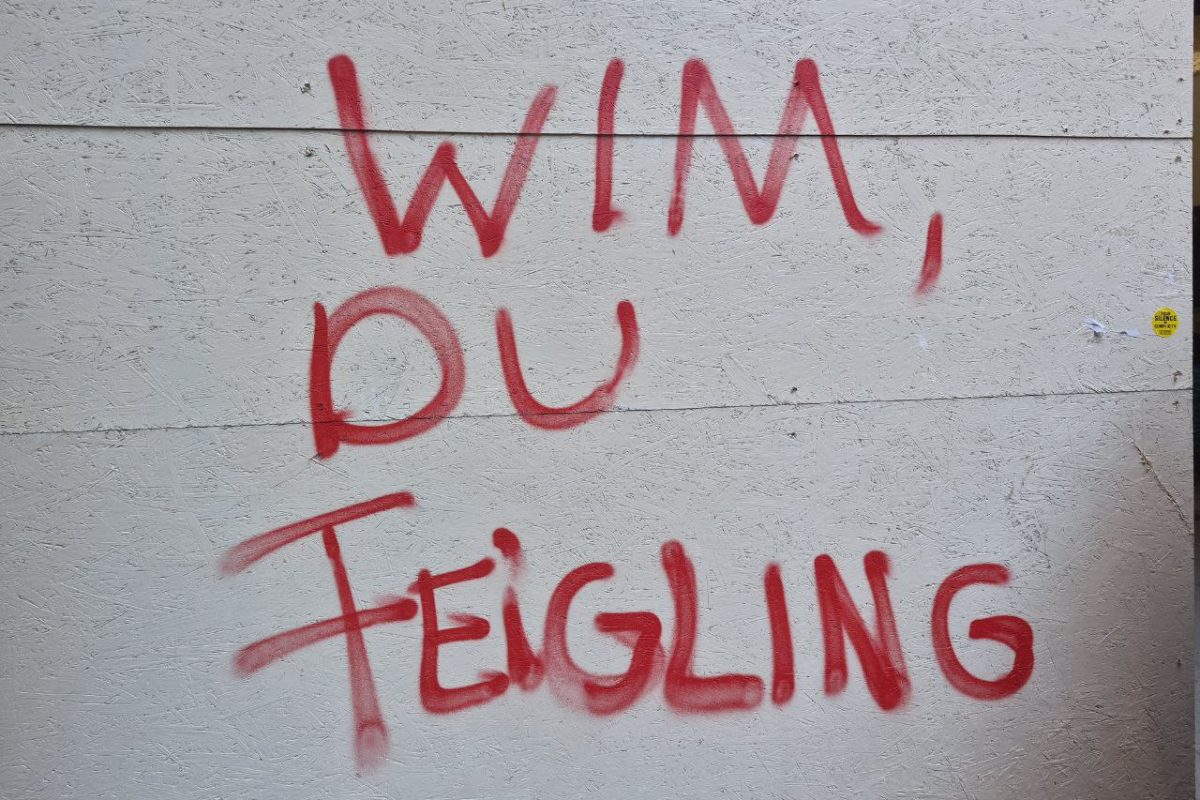

In Germany, Elbe’s claims of resisting academic orthodoxy ring especially hollow in view that pro-Palestinian voices are systematically silenced, and cast out of the academic circles, as the cases of Gassan Hage and Nancy Fraser make clear. Moreover, Elbe’s ideas align with the dominant political narrative that dismisses any criticism of Israel as antisemitic, while the tactic of self-victimization is less about defending academic integrity and more about reinforcing the power structures that postcolonial scholars aim to deconstruct. A clear example of how Elbe’s argument is received in Germany is its citation by far-right AFD politicians, who use his work to attack postcolonial theory and dispute Germany’s developmental programs, as well as the view of Israel as a colonial power. It is as if Germany is already seeing the first signs of a historical revisionism that will emerge in the coming years.

III. Against a “Manichean” worldview

Elbe accuses postcolonial scholars of promoting a Manichean worldview. While it is true that some scholars may overemphasize the crimes of European colonialism, his critique overlooks the fundamental purpose of postcolonial studies, which is to address both historical and ongoing injustices. As Pankaj Mishra argues, the legacy of colonialism continues to shape global power dynamics, reflected today in the unconditional support of Israel by this same “West,“ which makes PCS´s intellectual and political contributions crucial in challenging and exposing these enduring legacies.

Ironically, Elbe engages in a form of reverse Manicheanism, selectively attacking postcolonial scholars while ignoring critiques from Jewish intellectuals. Figures such as Judith Butler, Naomi Klein, and Norman Finkelstein have long critiqued Israel’s policies from a leftist, anti-Zionist perspective. Yet, Elbe’s oversimplification of “Jewishness” and how jews have to behave regarding Israel demonstrates his refusal to engage with the diversity of thought within the leftist tradition in general and PCS in particular. It highlights his ideological alignment with those who seek to protect Israel’s status as a Western ally and as an imperial protectorate.

IV. Hyperzionism

Elbe’s book reflects a significant fear among German “intellectuals” regarding the need to confront the legacy of their own hypocrisy and historical violence. As Rob Nixon discusses in Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, Western nations have long concealed the structural violence of their imperial and colonial pasts. Today, that legacy is starkly visible in the context of Gaza, the bombing campaign of Lebanon, and the recent war with Iran.

The recent statements by the new German chancellor, including “Israel is doing the dirty work for all of us,” are a perfect example of this imperialist alliance based on the continuous dehumanisation of the other, be they Palestinian, Yemeni, Iranian, or left-wing dissidents. Narratives like Elbe’s contribute to a broader ideological trend aimed at protecting Western interests, using intellectual discourse to maintain the neo-colonial and U.S. imperialist status quo.

Unsurprisingly, such views are prevalent within German academia, aiming to shape perspective of new generations of Germans in defense of the Western imperial legacy, warning against the “internal” and “external” threats, whether they be “hordes of immigrants” (from Arab countries seeking to enter Europe after their homelands have been destroyed), or the external threat from Russia. Apparently, Israel plays a leading role in this Western imperialist alliance against its “threats,” that the most warmongering German politicians and academics are unwilling to let it fall, showing a support that, due to its obvious hypocrisy and double standards, borders on the irrational and even fanatical.

This German hyper-Zionism, as Hans Kundnani describes it, even permeates leftist circles and the German Green Party. It is a strange nationalist tendency to perceive Israel as an improved version of the German self, a gross historical misrepresentation, particularly regarding the so-called Anti-Deutsch elements. For any outsider, it’s not easy to understand this strange kind of Freudian projection.

Final words

Ultimately, Antisemitismus und postkoloniale Theorie is not to be taken seriously as an “academic contribution”; instead, it needs to be seen as a piece of ideological propaganda designed to defend Israel’s colonial policies and maintain the Western narrative of self-glorification while “the only democracy in the Middle East“ continues in genociding Palestinians and bombing their neighboring nations. As the world grapples with the realities of colonialism and the ongoing genocidal campaign in Gaza, scholars like Elbe will find themselves increasingly isolated as their efforts to shield Israel and its ongoing crimes against humanity crumble under the weight of historical evidence and moral clarity. However, let’s be clear that this mixture of hyper-Zionism, contempt for historical facts, and moral panic, as Illan Pappe calls it, seems only possible in places like Germany.