Hi Ahmad, thanks for talking to us. Could you start by introducing yourself?

My name is Ahmad Al-Bazz. I’m an independent journalist and photographer based in Nablus City in the area of Palestine called the West Bank. I’ve been a member of the Activestills Photography Collective since 2012.

For people who don’t know Activestills, can you say a little bit about their work?

Activestills is a collective of documentary photographers that was created in 2005, twenty years ago. It has Palestinian members, international members, and those with Israeli citizenship who acknowledge themselves as being part of the settler society.

Activestills came to life when photographers first met in a village of the West Bank called Bilin during the weekly protests against the construction of the Israeli separation wall. They decided to use photography as a medium for political change. This was even before the era of Facebook and Twitter.

They wanted to express their political stance through photography. It started in a tiny village, but it has expanded to include almost everywhere in the area known today as Palestine/Israel.

So it’s not just the West Bank?

Yes, we have members who are in Gaza, the West Bank, and the territory of 1948 Palestine/Israel. It’s completely voluntary. People are committed. They go to the field almost every week.

You’re based in Nablus. For the past two years, we’ve been hearing lots about Gaza but much less about the West Bank

As we are speaking right now, in December 2025, the city of Nablus is a bit quieter than two years ago. This is because the little armed group known as the Lion’s Den, which was formed a couple of years ago in the city, is almost under control. It was semi-dismantled by both Israel and the PA (Palestinian Authority).

The raids are still happening almost every night, but they are limited to specific neighbourhoods where the Israeli military wants to do specific operations. But they move freely when they come. They enter the old town with undercover units. It is an easy task for them nowadays to enter and leave the city whenever they want.

Nablus and Hebron have the worst restriction of movement, because military gates around Nablus, for example, are always with soldiers checking cars. But there is a kind of a normal life in the daytime.

The district including the villages around Nablus is where the Israeli military has direct control. Israeli settlers live in the district, but not inside the city. This means trouble every single day. West Bank settlers have been increasing their attacks on villagers.

It reached a peak during the olive harvest season. It’s just these local stories here and there in every village where there is an expansion of a settlement. There’s some harassment, some tensions where the Israeli military is building walls. Every day there’s something. Since October 2023, Israeli settlers have completely displaced at least 44 Palestinian little villages in the West Bank, many of which are in Nablus.

What is the audience of Activestills?

Activestills made the decision to publish in English, because we believe this is the international language that will get you the biggest audience. After 20 years, we’re reaching people who are interested in the Palestinian-Israeli question. We also tried to caption some of our work in Arabic and Hebrew, so we get more local views, but we stopped temporarily because of capacity issues.

Is it mainly people who support you or are you also getting pictures to people who disagree with you politically?

We are mainly followed by people on the Palestinian side. Maybe that is natural because the collective has a political stance which attracts those who like that position, and who trust us enough to see more. Those who disagree with us may just follow for the sake of writing provocative opinions in the comments.

Activestills has an exhibition containing some of your works that is coming to Berlin. It was previously in Finland. How did that go?

Finland was in May this year. We have a member who is part-time in Helsinki, who said that there was a good number for such a small city. It’s not Berlin, it’s Helsinki. It also got some media coverage. The assessment was that because of what was happening in Gaza, people were more ready to go to a gallery and check out the photographs. It is also the 20-year anniversary of the collective.

In Berlin, it’s almost the same exhibition, with some little updates from May to December. Some stuff happened in the country. But it’s the same concept and the same theme.

The title of the exhibition is Documenting life, death and resistance in Palestine. What unites these different aspects of the exhibition?

Simply, this is life in Palestine. Our photographers do not approach Palestinians only as victims. Even some activist groups around the world deal with Palestinians by seeing them as victims. Maybe this is a safe, humanitarian point of view.

But Activestills started in a village where there were protests every week. People were clashing with the military, throwing stones. Documenting resistance to Israeli colonial rule is the core of our work. The exhibition is trying to show what’s happening in Gaza now—but also what has happened in the past two decades when the collective has been active.

Many people got introduced to the Palestinian question after October 7. They think it’s a state of war, and once there is no war, everything is kind of fine. We wanted to show them the accumulations that led to this, and to show that this two-year escalation is just part of what’s happening there.

By having a ceasefire, things are not going to be normal again because there is still the daily life of being under Israeli colonial rule in the West Bank, in Gaza and in 1948 Palestine/Israel.

What has changed as a result of the quote-unquote “ceasefire”?

According to our photographers in Gaza, air strikes and bombings are still happening—but at a different frequency. Around 320 people have been killed in Gaza since the ceasefire in October. This shows that the Israeli military is still operating, but they have more specific targets. It’s not the same scale.

Gaza is now divided into two parts. In one part, there is direct control. In the other, they just use air strikes. There are no troops working on the ground. It looks like this is the new style of post war, but we don’t know if this is permanent or just a transitional period.

People are still suffering. Housing units are severely damaged. People are living in tents. Our photographers are still doing the same work. Maybe they have a little bit more freedom to move, but they are still photographing this life of displacement with hardships.

Have you noticed any change in the West Bank?

No. The ceasefire in Gaza does not mean anything in the West Bank. Honestly, there is zero difference between one day before the ceasefire and one day after.

What is the role of photography in the Palestinian struggle? As I understand it, you see yourself more as an activist than a humanitarian.

Some of us see ourselves as activist photographers, some as biased journalists. There are different models. Photography is our tool with which we approach the political question of the country where we live. We aim to highlight what’s happening here. Some people will become aware of what’s happening here. Maybe they will feel attached, or mobilize. We don’t know.

To be honest, there is this sense of disappointment from our profession after the war because we feel that everything is over-documented in the country where we live, and maybe we are privileged compared to other areas where there are conflicts and wars and colonialism. Everything is well-documented, but there is so little change.

Many photographers, including those in Gaza, started developing negative feelings about their profession. They are asking: What else do we need to show for the world to react? What frame did we not have in the last two years? Because everything happened, even things that they never imagined they would photograph in their life because the model of Gaza was too extreme.

At the same time, we realised that this is an emotional moment for photographers who have been working for a while. But our work is kind of cumulative. We never managed to assess what impact we are leaving on people who are seeing our photographs. Political or media work is very long term. You just spread your messages, hoping for people to receive them.

Directly before this interview, I was at a new film about journalists in Gaza and you could sense a similar conversation going on. It’s not that the world doesn’t know what’s happening in Palestine, but the bombing continues. What motivates you to carry on?

There is nothing else you can do. At university, I dedicated most of my life to media/photography/documentaries. Either you stop or you continue. When I give myself a positive chance to check the impact of my work, by talking to people who have seen it, it gives you that fuel again to continue.

I like what I do and I want to continue until the last day of my life. I should not evaluate it by the impact of the next morning. It’s a very long-term process. It’s part of the struggle, which has been going on for over a hundred years. We have to keep trying. Sometimes, this is the point of our entire life.

Why should people go to the exhibition? What will they get from it?

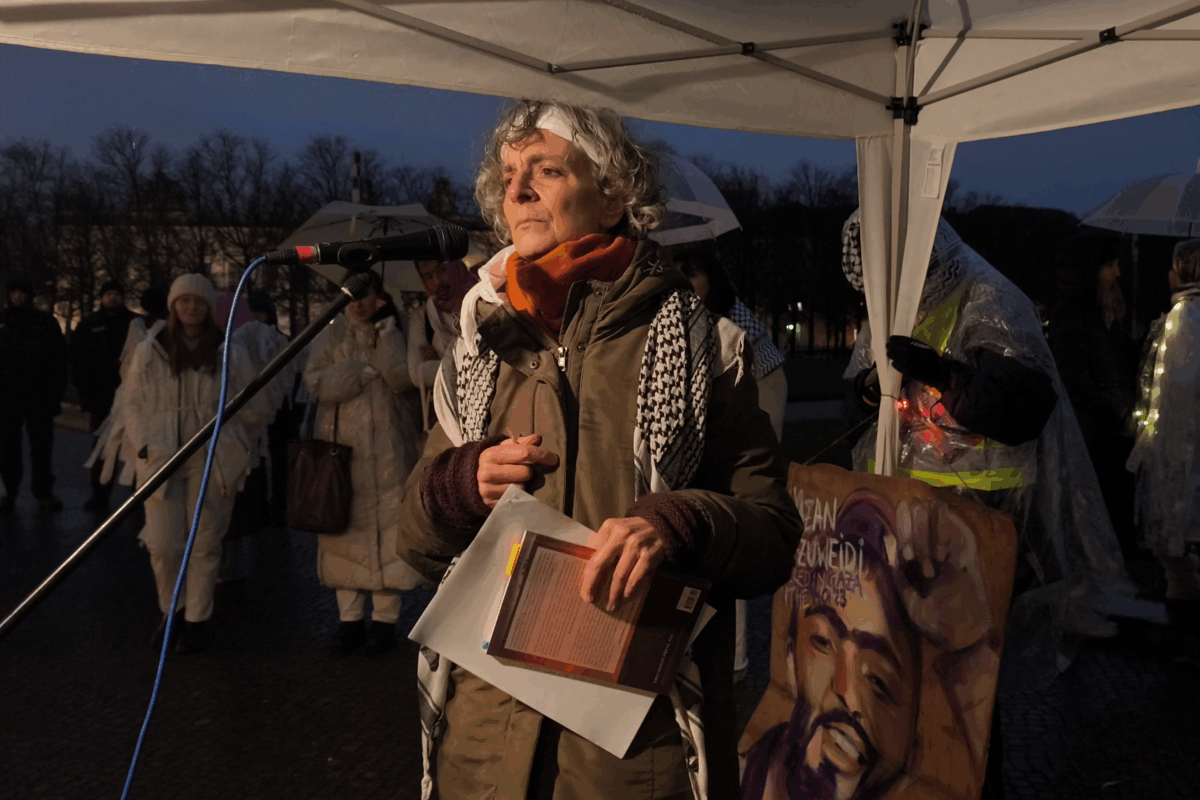

If you come to the exhibition in Berlin, you will get to see photographs taken by independent photographers on the ground who have their political stance and are delivering their message to you without any censorship by the media agency they are working for. You will get to see photographs from almost everywhere in Palestine/Israel. At the exhibition, people have the chance to chat with some of the photographers involved.

You will also get an idea of how Gaza is just a little part of what’s happening in the entire country. Palestinians in the country live under one system. It may be different in different territories. But Gaza is not the entire question of Palestine, although many people around the world know Gaza only.

I want to highlight that territorially Gaza is just 1% of the area of Palestine/Israel, especially when it comes to the media in Germany, who show a war between two conflicting parties—they depict it as terrorists fighting with a democratic state.

Will you be there yourself?

I’ll be there both for the exhibition and for the launch of my first photo book. The publisher is also coming, and we will have an event for the book on the 14th December. That’s also important for me on a personal level.

Tell us about the book.

It is called The Erasure of Palestine, and it’s the outcome of a three-year photographic trip that I did around the country, especially in the part that was occupied in 1948. This is the main body of the Israeli state today.

I went around dozens of these depopulated villages and neighbourhoods of the cities where Israel was established after displacing their residents. It includes Yafa—which is Tel Aviv today—Haifa, the villages around Yafa, the villages in the North, and the villages around Gaza. I wanted to highlight that displacement and the displacement that is happening now. And by now I mean 2022, 2023, 2024.

I was documenting the past and the present at the same time, to try and show that this is an ongoing process that has never stopped. I was arguing that if you want to understand the West Bank and Gaza, you need to start at least from 1948.

You need to understand why Gaza became a strip of refugees where 80% of the population are displaced people from where Tel Aviv and Israeli settlements are located today. This includes the areas where the Palestinian fighters attacked on October 7.

The book could be used as a POV lens to understand Gaza and what’s happening there. You can never start from 2023 or 2007. You need to understand the dynamic there, between the two sides of the fence of Gaza, the colonized and the colonizer.

And copies of the book will be available at the exhibition and at the launch meeting?

Copies will be available and some photographs from the book will be in one corner. The structures that remain in these towns and cities are quite shocking. Many people who only focus on the West Bank and Gaza will be shocked when they see a Palestinian mosque in today’s Tel Aviv. Many people ask me: Why is there a mosque in central Tel Aviv?

Then you tell them that 98% of the Palestinian Arab population of Yafa and its surroundings – which is today’s Tel Aviv – were displaced. And they ask you: Where did they go? And you say, mostly to refugee camps in the West Bank and Gaza, and that’s how Gaza was shaped.

This period of the Palestinian-Israeli question is being neglected on purpose. I think I know the reasons behind that, and that’s what I wanted to highlight in my book. And now, because of what’s happening in Gaza, I’m using that book to try and understand Gaza.

And the displacement of Yafa is still continuing through gentrification and “restoration” of buildings.

It’s still going on because those Palestinians who stayed in Yafa—and we are talking about under 3,000 Palestinians from 120,000,under 2%—were put in ghettos surrounded by barbed wire. And now, after 77 years of that displacement, Israel is coming to the owners and telling them that they are living in public housing and they need to leave for development projects.

People who understand the policy in question know that the core of this is displacement. Israel is just approaching Palestinians to relocate them using different pretexts. But they all lead to the same results—moving them to the smallest piece of land and giving the rest to Israeli settlers.

The Yafa people of Gaza used to live in Jabalia refugee camp. They had the Yafa neighbourhood. And that entire refugee camp was erased. You can see nothing of it today. That’s why people don’t connect. They don’t understand that those in Gaza are the owners of the land of parts of today’s Tel Aviv. They have been pressured and squeezed in that ghetto called Gaza Strip since 1948.

This is what we try as photographers to highlight, by showing what’s happening in Yafa, in Gaza, and in the West Bank, and sometimes in the diaspora camps in Lebanon and Jordan. We try to put it that way, visually.The Activestills exhibitionDocumenting life, death and resistance in Palestineruns from Saturday, 13th December until Saturday 14th February at Villa Heike, Freienwalderstraße 17. On Sunday 14th December at 7pm, Ahmad will be presenting his book The Erasure of Palestine, also at Villa Heike.