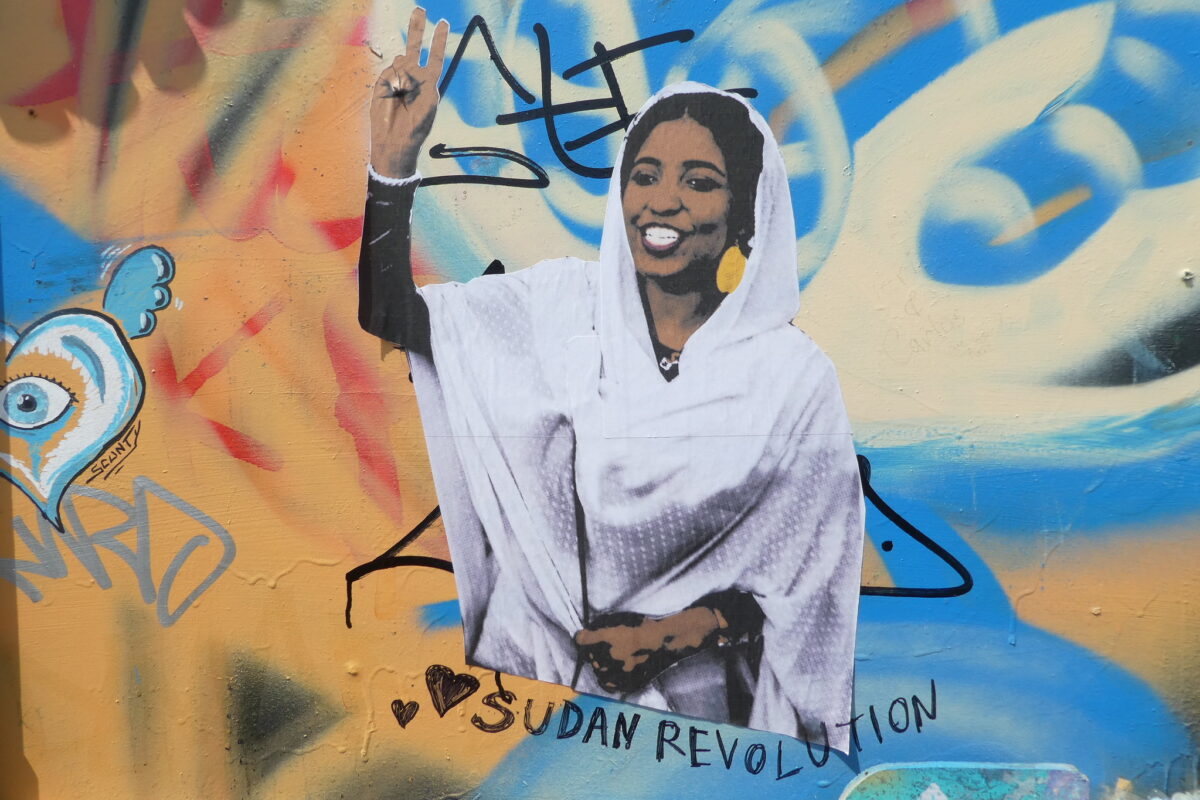

I would like to start this article by honouring the Sudanese revolutionaries, the unsung heroes of Sudan’s long road to freedom and democracy; the victims of the El Fasher massacre, the disappeared, the indigenous, the women, the children, the Kandakas, the Neighbourhood Resistance Committees (NRCs), the Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA), the Forces for Freedom and Change, the journalists, the doctors, the human rights defenders, the displaced, the boys in Greece and the Sudanese diaspora.

Just days after images captured in space recorded the blood spilled during the El Fasher massacre appeared on smartphones across the world, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), responsible for the atrocities, called for a three-month ceasefire while the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) refuse to accept any deal recognising the RSF as an equal political actor.

The news from the RSF, that many see as tactical deception, will provide little respite for the Sudanese population who have fallen victim to a vicious landgrab of their resource-rich country once again.

‘For any kind of peaceful solution, the RSF has to disarm themselves. What we have seen is that you cannot trust the RSF with weapons. They kill civilians, they rape women. They loot and destroy food and crops,’ says Sudanese analyst Yasir Zaidan.

The war that has been widely and deliberately ignored for over two and a half years—while other more Eurocentric wars have taken centre stage—is the biggest humanitarian crisis of our age.

It has cost an estimated 150,000 people their lives, with some figures suggesting the death toll may be much higher. It has forced 14 million people to leave their homes, has pushed 24 million people into food insecurity and famine, and has left 30 million in urgent need of humanitarian assistance.

The paucity of coverage of the war, global aid cuts, political and ethnic elitism, racism and international interest in the country’s resources have forsaken the Sudanese population and have contributed to global inaction to prevent the escalation that has at long last put Sudan on the agenda.

Despite warnings of possible genocide, the UK opted for the ‘least ambitious’ plan to protect civilians and prevent atrocities due to aid cuts over a year ago. USAID cuts left 80% of emergency kitchens unfunded, forcing 1100 kitchens to close. Although the UK has recently pledged to allocate £120 million in aid, the Independent Commission for Aid Impact reports that aid budget reductions in previous years have damaged relationships with partners and ‘calls for the UK to increase direct funding to local organisations and simplify its complicated compliance procedures to better support Sudanese-led responses’.

To put the urgency of the situation into context, the country blighted by the 30-year dictatorship under Omar Al-Bashir until 2019 already had some 1.1 million refugees and 3 million internally displaced people in September 2021, prior to the start of the war in April 2023. The day the war broke out, telecommunication systems were damaged and still remain unusable for the vast majority of the population. This has contributed to the difficulty of getting information out, exacerbated the logistical challenges of getting aid in and compounded the vulnerability of the civilian population, many of whom feel attacked by both sides—the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF).

A great number of our Sudanese comrades here in Berlin fled Sudan between 2003-2008 when the Arab nomad militia group, the Janjaweed, committed genocide in Darfur. To quell an insurgency by the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army and the Justice and Equality Movement (led by indigenous ethnic groups in Darfur fighting structural inequality and economic marginalisation), the Janjaweed, under the al-Bashir government, killed 200,000–400,000 non-Arab Darfuri people.

As news of the thousands killed by the RSF in El-Fasher in recent weeks reach our shores, reports on social media frequently call for a boycott of the UAE over its support for the RSF militia group through the supply of weapons and mercenaries in exchange for gold.

Meanwhile, other reports accuse the national army—the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF)—of being the other side of the same coin, a claim that has been fiercely refuted by some Sudanese commentators on social media platforms.

So, what happened to the 2019 Sudanese Revolution, who are the RSF and the SAF and how did Sudanese civilians get trapped between them?

After years of economic discontent, ethnic and gender inequality, and decades of conservative Muslim Sharia law, when Omar Al-Bashir announced he was running for an unconstitutional third term, the protest movement organised by the Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA), an umbrella organization of doctors, lawyers and journalists, started to gather momentum.

A revolution led by women

Following popular protests demanding an end to the 30-year long dictatorship and its sexist and oppressive laws, in which an estimated 70% of protesters were women, the SAF toppled Omar Al-Bashir in a coup d’etat in April 2019.

Sudanese women’s rights activist Asha al-Karib remarked:

‘The world-admired Sudanese revolution is marked by unprecedented contribution and participation of women throughout the country, including women from all walks of life. The participation of women is not a by chance event, as Sudanese women own a strong history of resistance in the face of dictatorships and patriarchy.’

The old guard

The subsequent self-appointed head of state Lieutenant General Ahmed Awad Ibn Auf, having previously served as the Defense Minister and Vice President in the toppled Al-Bashir government, refused to extradite Al-Bashir to the ICC for crimes against humanity and war crimes, leading to continued widespread protests.

The Transitional Military Council (TMC), the military junta that was established on the same day to govern Sudan, was equally denounced by activists. Leading anti-government protesters, the SPA, stated ‘the regime has conducted a military coup to reproduce the same faces and entities that our great people have revolted against,’ continuing ‘those who destroyed the country and killed its people want to appropriate every drop of blood shed by the great people of Sudan during their revolution’.

Auf resigned the following day and on 12 April 2019 Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, the former Inspector General for the Al-Bashir army, was announced as head of state.

Al-Burhan formally headed the TMC following the resignation of Auf and Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, also known as Hemedti, was appointed the deputy head, promoting the commander of the RSF to a key position in Sudan’s political sphere.

The aforementioned Janjaweed, responsible for up to 400,000 deaths in the Darfur genocide of 2003–2008, is a direct predecessor of the RSF—the new name being a simple rebrand.

The SPA and other democratic opposition groups called for the TMC to step aside in favour of a civilian-led transitional government, resulting in many attempts to disperse sit-in protesters outside the military headquarters in Khartoum. The TMC worked to end the peaceful sit-in with excessive force and violence and several people, including a pregnant woman, were killed.

What followed was a pivotal moment in the fight for democracy and a sign of things to come. In what became known as the Khartoum Massacre, on 3 June 2019, 120 protesters outside the military headquarters in Khartoum were killed and hundreds more went missing, with actual figures concealed with the help of internet blockages and the deployment of brutal military forces across the capital.

Unrelenting protesters took to the streets again on 30 June, finally prompting the international community to pressure the military into sharing power with civilian politicians in August.

Hope on the horizon

The Forces of Freedom and Change, a committee that coordinated the nonviolent resistance movement, and the TMC agreed to a 39-month transition period in July. On 20 August 2019 the FFC-nominated Abdalla Hamdok, who was appointed Prime Minister of Sudan.

The high aspirations for Abdalla Hamdok to bring about democracy in Sudan, however, weren’t to last. Though described as a ‘diplomat, a humble man and a brilliant and disciplined mind’ by the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa who agreed to implement a peace deal hailed as an ‘historic achievement’ by the UN Secretary-General António Guterres, the senior Sudan analyst at the International Crisis Group think-tank, Jonas Horner warned, the ‘devil will be in the implementation’.

Horner noted that ‘Sudan’s economy is in freefall and there has been limited international assistance, and none pledged specifically to support the implementation of the [peace] agreement’.

Moreover, researcher Ahmed Soliman stated that offering government jobs to rebel chiefs could ‘lay the foundations for democratic transition and economic reform’. Soliman said: ‘This requires the forces of change to share responsibility for implementing peace above their own interests and will also necessitate a commitment to devolve genuine authority to communities and people at the local level.’

Apparently unable to do so, the RSF committed atrocities across Darfur as a reprisal for the 2019 uprisings and the TMC’s military chiefs ‘undermined and side-stepped’ Hamdok’s leadership.

‘The armed Arab groups—the RSF as well as many less organised militias—have seized lands, livestock, and goods and see these as payment for their military undertakings to the Khartoum regime,’ Eric Reeves, a professor at Smith College and a fellow of the Rift Valley Institute research group told Al Jazeera.

Another coup dashes hope for democracy

And so, it wasn’t long before the Sudanese military under General Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan led another coup and took over the government in October 2021.

The majority of the Hamdok cabinet as well as pro-government protesters were detained and the prime minister, who called for the Sudanese to ‘defend their revolution’ was besieged in his home and pressured to support the coup.

The Prime Minister’s Office, along with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Information, refused to recognise a transfer of power to the military. The African Union suspended Sudan’s membership, pending the reinstatement of Hamdok, while Western powers stated they continued to recognise the Hamdok cabinet as the constitutional leader of the transitional government.

The SPA, the FFC and the Sudanese resistance committees refused to cooperate with the military coup organisers, leading further protests and strikes which spanned the country. Security forces retaliated by killing 15 members of the Sudanese resistance committee on 17 November 2021.

On 21 November, Al-Burhan signed an agreement reinstating Hamdok to restore the transition to a civilian government. This was met by fierce opposition from pro-democracy protestors who now refused any deal involving the military.

After two more were killed in pro-democracy protests and the already weak Sudanese economy steeply declined, Hamdok resigned as prime minister in January 2022, dashing hopes for democracy in Sudan.

Two war criminals fighting for supremacy

Oscar Rickett explains both Al-Burhan and Hemedti were fierce, reliable lieutenants of the Al-Bashir regime that had ‘plundered the resources of Sudan for decades’. Fearing a shift of power from the military elite to a civilian-led government, both ‘had to’ carry out the coup in order to cling to power and prevent being investigated and charged with war crimes.

With the prospects of a civilian-led transition to democracy eliminated, Siddig Tower Kafi, a civilian member of the Sovereign Council, commented that ‘it was becoming clear that the plan of Al-Burhan was to restore the old regime of Omar al-Bashir to power.’

And while Al-Burhan sought to centre power back to the elite ethnic groups around Khartoum, Hemedti, a Darfuri Arab, had become the leader of a powerful and brutal paramilitary force and had built a vast business empire. He had taken control of Darfur’s biggest artisanal gold mine in Jebel Amir, and his family company, Al-Gunaid, became Sudan’s largest gold exporter.

Writing for Al Jazeera, Jérôme Tubiana explains:

‘This is not just a war for power between two generals, but rather one between the two heirs of the not-yet-defunct regime: the legitimate and illegitimate sons of one father, at the head of two fundamentally different forces. On one side, an army long headed by officers hailing from Sudan’s ethnic and political centre (the northern Nile Valley); on the other a paramilitary corps that is the latest avatar of Darfur’s Arab militias.’

Arabs and non-Arabs caught in the crossfire of supremacy

Omar, from the capital of Hemedti’s Mahariya tribe, Ghreir, an ‘old Arab settlement and stage post for nomadic camel herders’ where Arabs and non-Arabs long lived side-by-side, explains that the region became the heartland for Janjaweed recruitment in 2003.

Omar and some other members of the Arab tribes rejected joining the Janjaweed and joined the rebels instead. Feeling manipulated by the government and not wanting to be associated with the Janjaweed, he explains how students understood that ‘the government was instrumentalising their communities to kill their non-Arab neighbours.’

When Hemedti, who attended school in Ghreir but dropped out of primary school to become a trader around the age of 8 or 9, rose to the ranks of leader of the RSF in 2013, he continued aggressively recruiting from his own tribe and taking rebel territory.

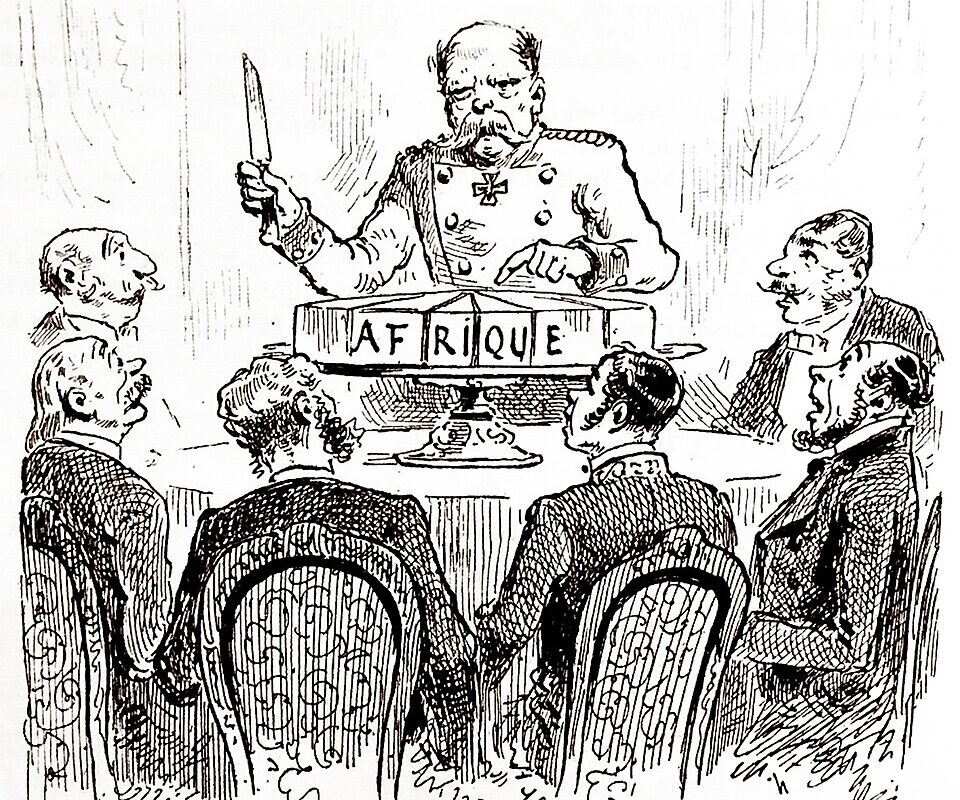

International vultures and hypocrisy

Foreign interests, extraction and colonialism—spanning over a hundred years, with Anglo-Egyptian control over Sudan spanning from 1899 to 1956—continue to this day.

The complex web of support for the two warring parties, as explained in this article include Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Qatar, Algeria, Libya, the UAE, Turkey, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Russia, China, Chad, and South Sudan, have further complicated peace talks and neglect the interests of Sudanese civilians.

Recent evidence showing UK manufactured weapons have surfaced in Sudan proves the UK’s complicity in the atrocities. In breach of its own arms trade rules the UK continued to sell weapons to the UAE, known for being a diversion hub for weapons to conflict zones.

The UK’s failure to invite any of the principal Sudanese actors or members of civilian society, while inviting the UAE to the ceasefire conference in April, is symptomatic of the wider neocolonial narrative. Such actions make the call for peace by UK Foreign Secretary David Lammy ring hollow:

‘The biggest obstacle is not a lack of funding or texts at the United Nations; it’s lack of political will. Very simply, we have got to persuade the warring parties to protect civilians, to let aid in and across the country, and to put peace first.’

While we all seek to differentiate between the ‘bad guys’ and the ‘good guys’, ultimately the horrors that are unfolding in Darfur reflect the story of centuries of colonialism, supremacy, capitalism and land appropriation.

Silencing the voices of the indigenous, peaceful resistance and of the ancestral owners of the land perpetuates the supremacist violence that has cost so many Sudanese people their lives and loved ones.

Their resilience untold.