Hi, Jacob, thanks for talking to us. Can you first introduce yourself?

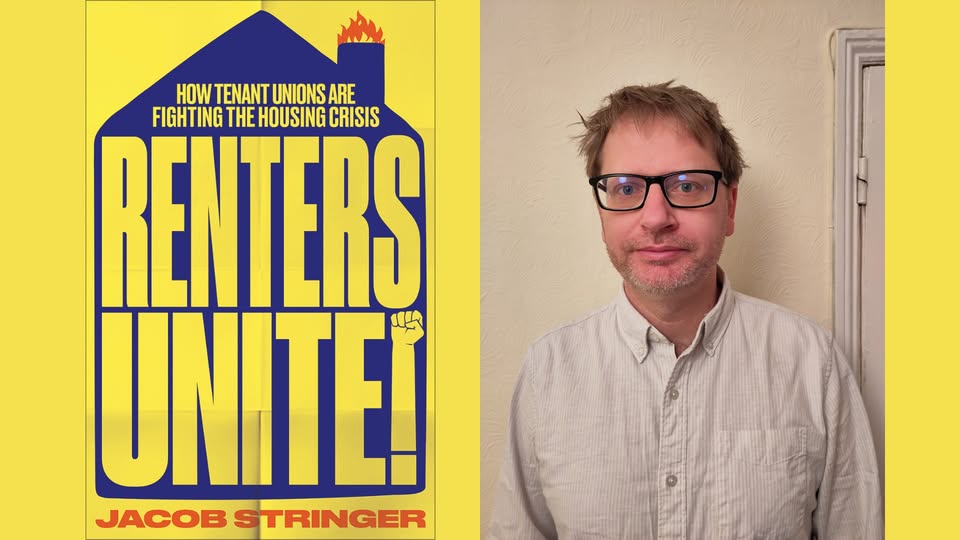

I’m Jacob Stringer. I organised for five years or so with London Renters’ Union and then I did a PhD on tenant unions. I just wrote a book called Renters Unite, which is an overview of the new wave of tenant organising in the Global North.

When you say the Global North, where exactly do you mean?

The book covers Europe and North America. Realistically, I didn’t have the opportunity to go to Australia or other more far-flung places. But it’s a wide variety of countries and experiences.

Tenant unions have been springing up across Europe, across different parts of the UK. There are city-specific unions, so I talk about the Manchester tenant union. Then some countries have a national tenant union. Ireland has one called CATU. It’s also happening in the Netherlands, in Germany, in Poland.

In the US, there’s a huge number of new tenant unions, which tend to be city based. I talk a lot about the Los Angeles and Crown Heights (Brooklyn, New York) tenant unions because they’re particularly interesting examples.

You say there’s a new surge of tenant unions. Why now?

It’s happening now because many places are experiencing what we loosely call a housing crisis. “Housing crisis” is a strange term, because usually you use the word crisis for something that doesn’t last long and then you resolve it. That’s not what’s happening with housing.

In many countries, people are facing ridiculously high rents for very low-quality accommodation. There’s a lot of overcrowding in the UK. A lot of low-income families are pushed into “temporary” (accommodation) in which you can actually be for years.

It’s better to talk about housing injustice because the reality is that it’s a crisis for tenants, but it’s not a crisis for landlords and it’s not a crisis for a lot of the establishment. The reason it continues is because there are people benefitting from it.

The increase in housing costs and degradation of conditions has now been going on for decades. Housing has become a very intensive site of exploitation in the current moment and often the big investment funds see more opportunity to extract money from housing than they do from setting up a factory, say, particularly in de-industrialised countries like the UK.

Around the world, people are starting to say that this can’t continue. We’ve got to do something about this. We’ve got to take the fight to the landlords and to the establishment who are keeping things going this way.

After Occupy, for instance, a lot of people started thinking about more permanent organisations, which could gather people together in communities of solidarity. Tenant unions just became the answer in a lot of different places.

You’re talking about the Global North where the population is stable. Free market theorists say that supply and demand means that housing prices should remain as stable as the population. So, what’s behind this surge in rent costs?

That depends on who you ask. There are some on the UK left who say that we don’t need to build more housing in the UK. I disagree with that. As an example, housing has been quite tight in London, and over the last few years net migration into London has been half a million people. When that’s happening, I do think is necessary to build more housing.

However, at the moment, building more housing doesn’t actually make prices cheaper, and part of the reason for that is because more and more capital is flowing into housing. It is becoming really attractive to big real estate investment trusts, private equity even.

Housing prices are not just about supply and demand. It’s also about who has the capital to put into it. So, what’s happening in the UK, and I suspect in a lot of countries, is that the landlords have more capital than ordinary people. They out-compete everyone.

People also occupy housing less densely than they used to. In a lot of rich countries the boomer generation is coming into retirement. In a more rational housing market, when you retire and your kids have left home, you might sell your three- or four-bedroom house and move into a smaller place. But what’s happening is that for a lot of retired people, their house is their main asset, which gives them a lot of security.

It’s not just retired couples. Single people are also living in large family houses. The boomer generation is called that because it was so large. Now enormous numbers of older, retired people who don’t really need very much space are living in these big houses. That’s a more peripheral effect, but it all comes into the mix.

In the UK, a big factor is the sale of social housing. The purpose of social housing was to undermine the landlord class and provide cheap, quality accommodation. Nobody would dream of paying large amounts of money to a private landlord. A big project of neoliberalism was to sell off a lot of public housing.

People talk about this a lot in the UK. But there are other countries that haven’t sold off their social housing. Spain never had much social housing. France hasn’t really sold off much. Yet they still have housing crises. There are a lot of factors in play. But the really short answer is property becoming attractive to capital.

How are people resisting the rise of rents?

The short answer is that they’re setting up tenant unions.

What does a tenant union do?

A tenant union is a membership organisation that collectivises people’s struggles around housing in a similar way to a union collectivising people’s struggles around the workplace.

A lot of people were involved in smaller struggles before over a particular building or a particular housing estate in London. And people saw that there was a need to build larger organisations, to really build broad-based solidarity. And so, these tenant unions have arisen. Usually, they have a fee-paying membership. So, they have resources. Some of them have paid staff, others don’t.

But all the tenant unions have two main tracks that they’re working on. One is solidarity around particular conflicts with landlords. Sometimes that’s just an individual having a conflict with a landlord, sometimes it’s a whole building. A lot of the base organising of the tenant union is around those conflicts.

Another track is campaigning. Most tenant unions are involved in campaigning for things like rent controls or ending no-fault evictions, which has just been won in the UK. They are also campaigning at local level around regulation of landlords and things like that.

A lot of the tenant unions are also trying to build local communities of solidarity, so that neighbours get to know each other and people do not live in isolation. Most tenant unions see themselves as part of a wider political project of trying to challenge individualism, making sure that people don’t feel that they’re facing the troubles of life alone.

London Renters Union, for example, tries to make its events enjoyable. It’s not just about having meetings. We have food in most of the branch meetings, we put on events people can enjoy coming to. It’s about building relationships and trying to spread networks of solidarity through your community.

You’re talking about moving from smaller, localised struggles to larger ones. It’s obvious how that works in social housing if everyone has the same landlord. How can people with different landlords work together?

This is a particular problem in the UK, where ‘landlordism’ is very dispersed. Most landlords in the UK only own one or two houses. Most blocks are owned by the local authority. This is something that London Renters Union has had to address by developing a narrative of mutual aid: “We’re going to help you. You’re going to help with someone else’s struggle.”

We sometimes put quite a lot of work into just one individual’s case. Sometimes that person then leaves the union and never sees us again. It’s always a little disappointing when that happens. But a lot of people don’t. They stay and want to fight other people’s cases as well.

The collective action element comes in with individual cases, where a tenant union decides that we will bring pressure on either the landlord or the agents in a collective way. We might write a letter to an agent who is failing to do repairs on a house. Then we turn up at the agent’s office with 20 people and say: “here are our demands. We are not going to go away until you sort this out. We are going to make your life miserable until you sort this out.”

That can be very effective. It doesn’t always work. Any workplace union could tell you that you don’t win every fight. But London Renters Union has got pretty good at winning.

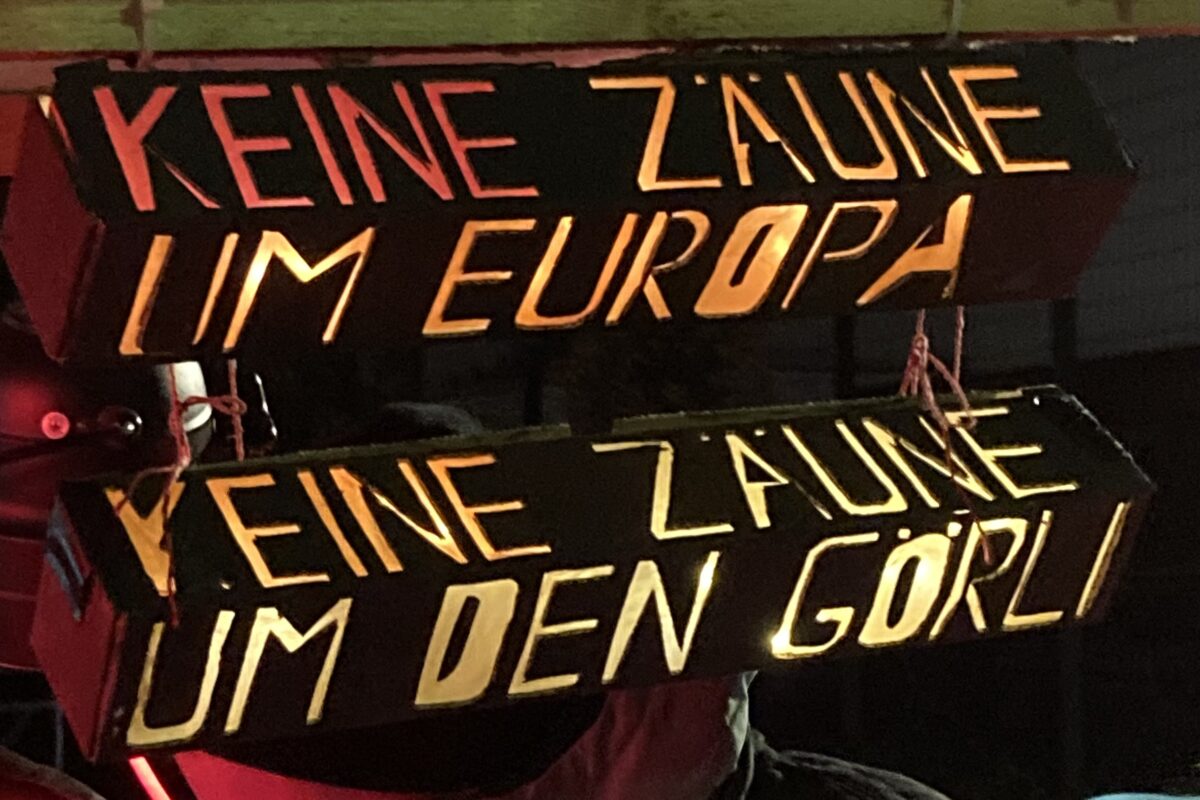

Part of your book covers Berlin, where most of our readers live. As an outsider, what’s your perception of the housing movement in Berlin at the moment?

On the one hand, the housing movement is stronger in terms of numbers than in London. Berlin has had strong housing organising for a while. On the other hand, it’s very apparent that a lot of the attempts to stop gentrification have not, in fact, stopped gentrification. Many attempts to save sites which were available for community use have failed. The rents keep going up. There are some really wonderful successes, but it feels like not enough.

I talk a little bit about the expropriation campaign in the book. That’s a wonderful, inspiring campaign in many ways. A lot of people around the world read about it and go: “Wow, we wish we could achieve something like this here”. On the other hand, it also feels painfully slow to many people. It also feels like it will only help a limited number of people.

In Berlin, everyone knows the figure 59.1%, which was the number of people who voted to expropriate the big landlords. But after we won the referendum, the Berlin government just simply ignored the decision and carried on as before. What can we do to ensure that we do not just win votes, but get real change?

Barcelona has suffered some similar disappointments, where the housing movement got their people into the city government for a few years, who managed to make some changes, just not as many changes as people were hoping. And there’s still a housing crisis in Barcelona.

Now that that left wing government is out of power, they’re asking themselves: how is it that we could get so far and still not really make a big impact on housing for ordinary people? I think the difficult but true answer is that it’s hard to see how housing issues will really be resolved without undoing the wider neo-liberal governing conjuncture and taking on the powers of finance at the national and international level.

It is a huge struggle, but we have to face up to the reality that to make changes through legislative methods, these wins at local level are often not enough. You’re going to have to get wins at national level and get your people into government at national level.

But even then, you’re going to find that you’re up against the power of capital and the finance power block. The reality is that we’re not going to solve housing crisis until we are strong enough to take that on. That’s quite a difficult message, because it feels a long and painful job to take on those powers. But I do think it’s going to be necessary.

The strongest interim measure that you can take, without entirely overthrowing the current order, is to get public housing built in very large quantities. But the problem with that is you’ve got to get the finance for it. And as long as governments are pretending that austerity is the only option, it’s very difficult to get the finance for that housing.

Building more public housing is not a full answer, but it’s a good halfway house. And even to get that, we’re going to have to undo the entire austerity narrative that has bedevilled Europe for the last couple of decades. We’re going to have to say: “this scarcity you’ve created is false. We do have the resources to build the public housing we need”. I think it’s achievable, but it’s a big, big project.

What would you say to the people who say higher rents are not because of landlords or austerity. They’re the fault of migrants?

Of course, it is not migrants’ fault that house prices go up. This is about the scarcity narrative that years of austerity has induced. People are convinced that there’s very scarce resources to go around and that there’s not enough to share with new people coming in.

That narrative is entirely false. In the case of London, which has had a lot of migration over the last few years, you do need to build more housing, but that housing needs to be public housing. It needs to be aimed at the working-class, low-income people who need it the most.

In many cities, the population is not increasing. In that case, it’s very easy to show it’s nothing to do with migrants. It’s to do with the grip that landlords and capital in general have over the housing economy.

The main thing we have to do around this migration issue is destroy this idea of scarcity. We live in very rich countries with enormous access to resources. We can share these resources around, as long as the people at the top aren’t hoarding too much of it. And that’s got to be the main message.

Where can people get hold of your book?

Renters Unite is published by Pluto press, and you can order from their website, or you can just go into a bookshop and ask them to order it for you.

Is there anything that you’d like to say that we haven’t covered?

I would say, join a tenant union. And if there isn’t one near you, start a tenant union. Because this is the fight of our lives. We’ve got to win decent housing, or we can never live well.