Hi, Lucas. Thanks for talking to us. Could you just briefly introduce yourself?

I’m Lucas Maier. I’m 32 years old. I’m based in Berlin, and I work as a journalist.

And at the moment, you’ve got an exhibition at Regenbogen Cafe.

Yes, I do. It’s about Sea Punk 1, which is a sea rescue vessel in the Mediterranean. I was with the crew in January this year.

How did you get involved with the Sea Punk 1?

I wrote them a message because I had some free time. I was taking some months off work, and I asked them if it’s possible to help them with their media.

Let’s talk about the subjects of your photographs – the refugees crossing the Mediterranean. There’s been a lot of media discussion of refugees being a problem, a burden, or people coming here trying to disrupt our country. Who are the people and why are they on the little boat in the middle of the Mediterranean?

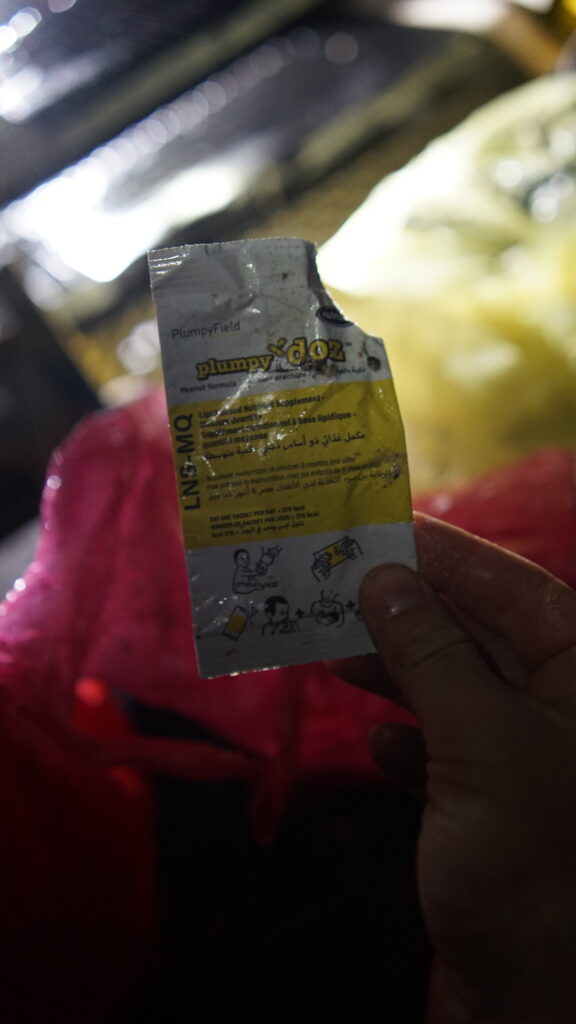

It’s not one kind of people. It’s super diverse. I think the youngest person I’ve seen was younger than one year, the oldest was most probably over 80. They were also really mixed between women and men.

What they have in common is that they live in shitty situations, and want to have a better life, a free life. If they come from certain countries, they have no other option than to go over the Mediterranean with a fucking rubber boat or something. It’s the only choice they have.

A lot of the people in your photos were coming from Libya. How did they get to Libya in the first place?

Super different. Some told us that they walked there from African countries where there is a land connection. Others were, for example, from Pakistan. A lot of people also go to Tunisia nowadays because it’s less dangerous, with fewer chances of being thrown into prison.

Once they’re finally on the Mediterranean, what are the problems that they encounter there?

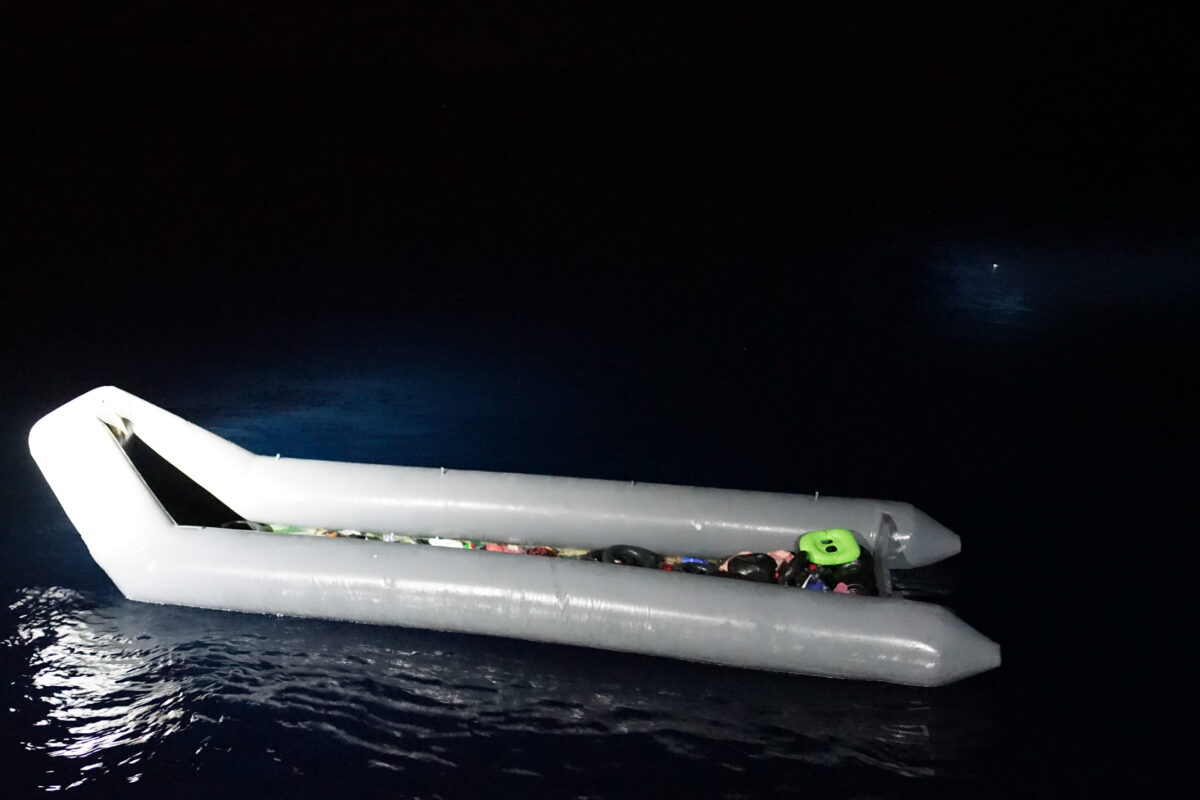

There are a lot of different problems. First of all, they have no captain on the boat. It’s just random people who are forced to drive. If you don’t know how to drive a boat in the middle of a big ocean, it’s not the best situation. You have no navigation system at all, because mobile phones do not work out at sea, and most of them are in a plastic case, so you can’t use them.

They’re left to navigate using the sun and the stars. And this is super dangerous, because it can extend your journey by days or weeks, and it is high likely that you would run out of gasoline. If that does happen, you have no power to fight the waves anymore, which makes it highly likely that your boat will capsize. And if the waves get too high, these unseaworthy boats will just capsize.

Then you have double decker boats, where people are trapped inside, and some of them die because there’s not enough oxygen, or due to fumes from the motors. Some get fuel burns because when you mix sea water with gasoline it becomes highly toxic, and results in really bad burns.

Then they reach Europe. I guess, theoretically they could land in different countries. Is there a difference between the way they’re treated in each country?

I mostly encountered people going to Italy and Malta. I think it depends a lot on whether you’re out in the Mediterranean, and if you’re able to leave the Libyan SAR Zone. If the Libyans pull you back, you have to go through the fucked up situation from the beginning again – and encounter even worse hardships.

Italy has, for example, the Piantedosi decree from the fascist Meloni, which overrules international sea law and says that they can decide where you should bring people saved by sea rescue. Back in the day, it was normal to go to the next port, because it makes sense to go to the next safe place. But nowadays, it takes days to bring people onshore, with legislation instated just to block the NGOs from what they are doing.

Speaking of NGO, which NGOs were you working with?

Sea Punks is a smaller NGO with a smaller vessel, compared to Sea Watch or Ocean Viking. I think the boat is a total 32 meters, and can carry up to 14 crew members and can take up to around 40 people at maximum capacity.

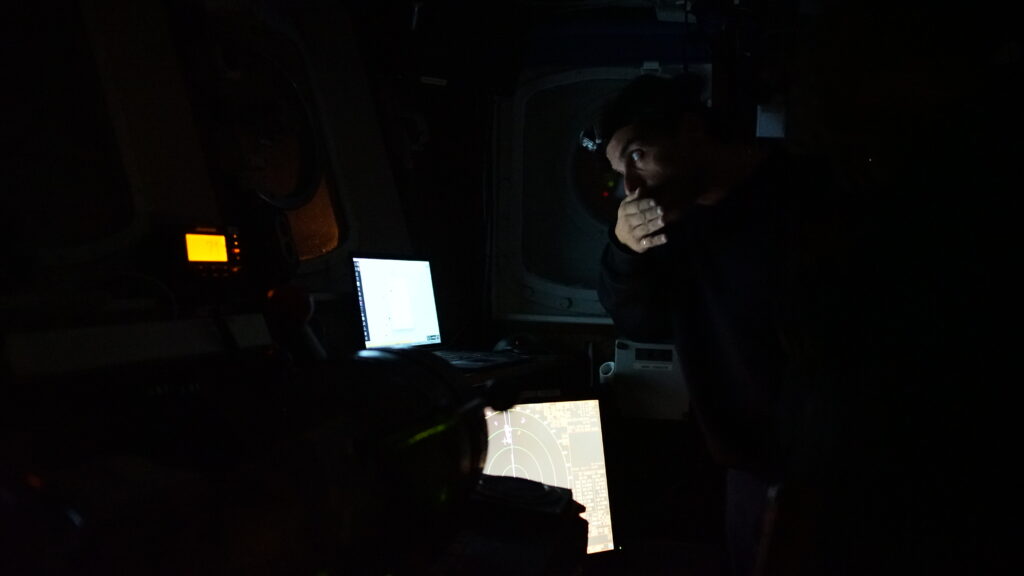

The boat is mostly made for accommodation or assisting situations. Because it’s so small, it’s not that easy to carry people. So if it encounters a boat which is not sea worthy, people on the Sea Punk can speak to them and give them proper life jackets. And if a boat runs out of gasoline, they organize help from Italy or Malta so that the boat doesn’t capsize and get to Charlie Papa.

Are they able to do this without being impeded by the Italian or Maltese governments?

Yes. You need to have a lot of law stuff in mind and in focus. That’s why you also get trained at the beginning. Every step is done legally, 100% correctly. Until now, there have been no bigger problems with the state. There has been no detention yet. Let’s see what the future brings.

Let’s move onto your work as a photographer. What difference do you think an exhibition like this can make?

I think it can bring the situation to the people. Especially in Central Europe, it’s far, far away – not only in distance, but also in people’s mindset. Most people here can’t imagine how it is to stay for days on such a boat and nearly die.

For the people who died while I was there, it’s the only way to show that they died and that this is happening. If we hadn’t been there, they all would have died, and nobody would have even known. It’s such a huge sea, and if you don’t find the boat, it’s just gone.

The exhibition currently is in the Regenbogen Café, where most people are at least aware of refugees and are generally on their side. How can you get across to a wider audience of people who are either not aware of refugees or are aware and don’t want them?

This is the first time I showed this exhibition, and it’s a nice environment to have it in. But of course, in the future, I also want to go to places which are more conservative, encounter people without an explicitly leftist mindset. Maybe at a church or similar. I want it to lead to discussions which are outside the box.

Do you think you’ve got hope of getting venues like this?

Actually, I know some people in person. After a quick chat with them, I think it could be managed. It’s not that hard for me to find other places.

If someone goes to the exhibition and thinks “This is terrible, I should do something,” what should they do?

First of all, they should speak about it. In Germany, we have a really strong rise of the right wing. It is becoming more normal in society to say: “It’s ok that they are dying. It’s just refugees.” And that’s not okay.

Of course, it’s always good to support NGOs with money or with volunteer work if you can. Sometimes it just takes little steps to change the world a little bit more.

What about the people who say: “They’re having a bad time, but Germans are having a bad time as well. Germans are losing the jobs. Germans are poor.” Why should people worry about refugees?

Firstly, there’s a difference between losing your job and losing your life. We had one family who lost all three of their children in one day. Losing your job is nothing compared to that. I think it says a lot about white privilege to think that way.

If you have faced situations like that, it can help you deal with your own problems at home, because you come to appreciate that there are people who have a much harder life than you and have problems that threaten their survival. Of course, losing a job is not the best situation, but it’s also not the worst.

Part of what you’re doing is talking to people with terrible experiences. Of course, it’s worse for them than it is for you. But how do you sustain yourself in terms of just viewing all this misery?

Before I got there, I prepared for the worst case scenarios – if it comes to difficult situations, I always prepare like that. It helped me a lot. Beside that, it was good to have the support of the crew. We helped each other, and talked to each other. We also had two days of psychological support at the end.

How does someone become a crew member for something like this?

There is a form on the website. There are different positions on board. For some, you need to be sea worthy with certificates. For others, you don’t. As a media person, I just wrote a message to them and said: “Here’s my CV. You can check if it fits what you need.” Then they called me back and invited me.

The vessel is not always at sea. There is a lot of time spent in port. And people can help with maintaining the boat. A large part of the work is maintaining the boat so that it’s still seaworthy.

What are your next plans? How can you make your photos available to a wider audience?

My next step is to put the exhibition online. I got a lot of messages from people saying that they’d like to see the photos but it’s not possible for them to come to Berlin.

Do you have a chance of showing in other cities?

Yeah. I’m in talks with one place in Potsdam, and maybe also in my home town in Bavaria.

One last question for the Berliners. How long is the exhibition going on? Where can they see it? And when?

It’s at the Regenbogen Café, next to the Regenbogenfabrik in Kreuzberg. It is on until the last weekend of September, during the normal opening hours, which are on their website.

If people want to support you personally, how can they contact you?

My contact is written at the exhibition, so they can just contact me. But at the moment, I don’t need that much support. At the moment, people should really be supporting the people who are drowning in the Mediterranean.

All photos: Lucas Maier. These are just part of the exhibition which you can see until September 27th in the Regebogenfabrik Café, Lausitzerstraße 22a, The café is open on Tuesdays from 12:00 – 18:00, and Wednesday and Fridays from 15:00 – 22:00