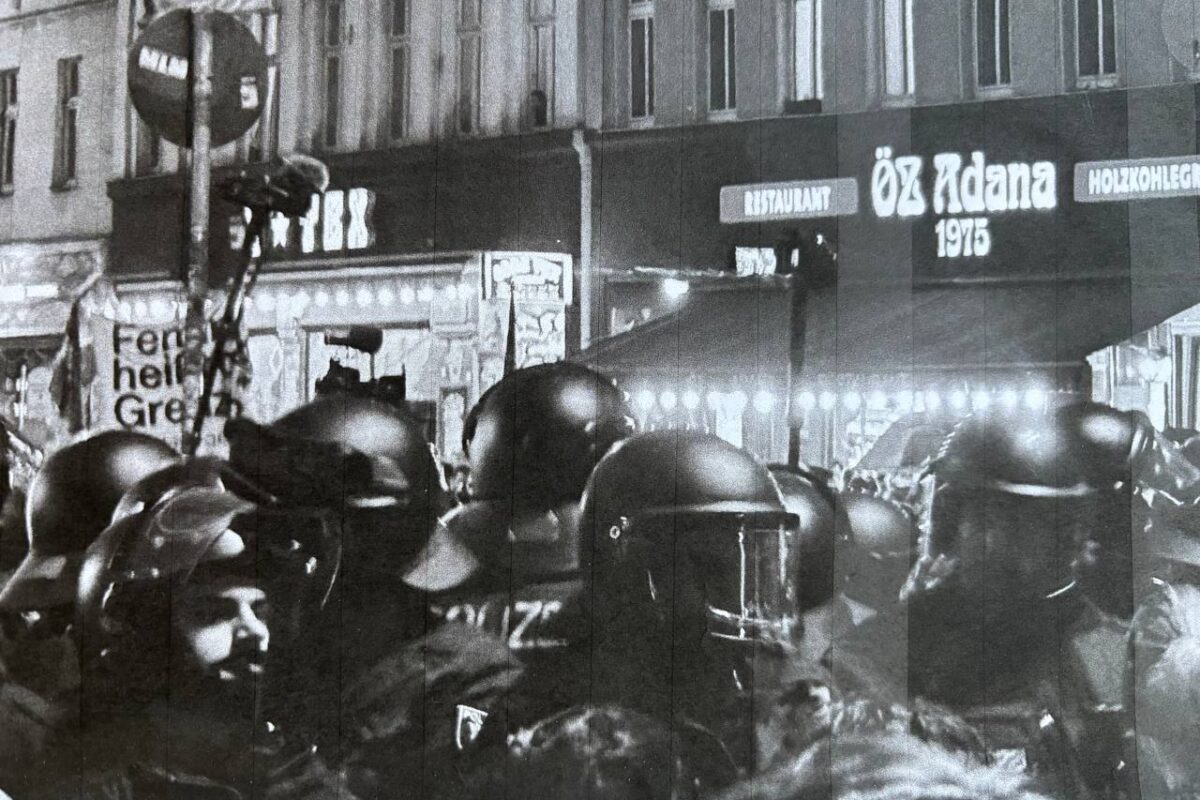

In Germany, repression of Palestine solidarity doesn’t just wear riot gear. It comes in press briefings and policy memos, in visa denials and cancellations, in shifting legal justifications that twist basic rights into instruments of exclusion. A protest chant becomes evidence of extremism. A campus lecture is ruled “too political.” Decades-old slogans are reclassified overnight as support for terrorism. It’s not incidental. It’s systemic and a multi-layered effort to stigmatise, intimidate, and isolate those who speak out for Palestinian rights.

Part of an ongoing colonial pattern, this climate didn’t appear overnight. The European Legal Support Center (ELSC) was founded in 2019 to initially track how Palestinian civil society organisations in Palestine were being targeted by European governments. But as the same strategies of repression began to take root in Europe, and particularly in Germany, the ELSC broadened its focus to include the growing crackdown on anyone speaking out for Palestinian rights.

Revealing the institutionalised criminalisation of Palestinian solidarity, the ELSC’s Index of Repression in Germany currently documents more than seven hundred incidents affecting thousands of people, across multiple categories.

We spoke to Layla Kattermann and Sophia Hoffinger of the ELSC about how the index came to be, how repression in Germany has intensified since October 7, and why tracing both the incidents and the shifting legal framings is key to understanding how silencing becomes socially and institutionally normalised.

Hi, please can you introduce yourselves and what your roles are in producing the Index?

Layla: My name is Layla Kattermann, and I’m the Monitor Project Manager at the ELSC. I’ve been managing this project for a couple of years now. In the beginning, it was just me, but now we have a full team of monitor officers and data researchers in several countries.

Sophia: I’m Sophia Hoffinger. I joined the ELSC this year as the Germany Monitor Officer, working with the monitor and research department. I’ve been involved in data verification and writing summaries of some of the selected incidents you see on the platform.

You’ve been tracking repression since 2019. How did the ELSC’s monitoring work develop into what is now the Index of Repression?

Layla: Since the establishment of the ELSC in 2019, we were very aware of the need for this kind of research, especially in light of the attacks that Palestinian civil society organisations in Palestine were facing from Europe. So initially, we were tracking the oppression they’re facing before expanding the research to also include the repression of people who speak out for Palestine across Europe.

At first, we had a strong legal focus. We looked at how the law is used, how it’s interpreted, and how it’s developed to violate fundamental rights when it comes to Palestine. But a couple of years ago, we started to include forms of repression that don’t make it to the courtroom and that don’t cite any law or policy. So now we focus more on the impact of smear campaigns, and many other forms of repression that lead to mental distress, financial and professional pressure, and ultimately, self-censorship. And of course, we also try to track who’s behind the repression.

Did you see a shift in how repression presents itself in Germany after October 7?

Layla: In terms of mechanisms of repression, no. The mechanisms existed well before October 7, but because the movement has grown, what changed was the scale and the visibility. On the legal level new policies were introduced and existing ones were reshaped or reinterpreted, but we didn’t have to invent new categories or allegations.

Sophia: Yeah, maybe to just give some examples, after October 7, we saw a lot of emphasis on different kinds of parliamentary resolutions encouraging the state to use all mechanisms of migration law and criminal law to persecute people in the name of fighting antisemitism.

Layla: What we’re seeing now is unprecedented in terms of scale and visibility, but it’s a continuation of trends that began years ago, just like the implementation of the IHRA definition, anti-BDS motions, and the criminalisation of political slogans. Take “From the river to the sea”: people were charged for it before October 7 under allegations of antisemitism or incitement to hatred. Now it’s being treated as a symbol of a banned organisation. So the repression isn’t new, it’s that the legal justifications are shifting. There have been constant developments just to keep violating fundamental rights.

Sophia: Right, and those shifts in framing are important to track. In 2019, BDS was criticised for supposedly echoing the fascist-era boycott against Jewish citizens. After October 7, it started being described as a form of secular Palestinian extremism, which is something very different. And just recently, it was labelled “anti-constitutional” by the domestic intelligence agency. So we ask, where did this allegation start? Why did it change?

Has there been any public or institutional pushback on this constant reinvention and reframing?

Layla: There have been some. For example, last summer, when the German domestic intelligence agency, the Verfassungsschutz, designated BDS a suspected case of extremism, the UN Special Rapporteur on counterterrorism and human rights wrote to the German government, asking them to justify why, but the concerns weren’t directly addressed. So yes, there has been pushback, but it hasn’t been widely picked up yet. I think it’s also becoming normalised how repressive Germany is, which is a problem. Activists in Germany accept a lot more forms of repression that shouldn’t be accepted. So much so, we’re seeing people in other countries say “Well, it’s not as bad as Germany yet.”

In what other ways have you seen repression becoming normalised?

Layla: A good example is the Berlin Four, the EU and US citizens who faced deportation. In the end, they won their cases and weren’t deported, but the fear had already been instilled. That’s the point: you don’t have to deport everyone. Just one or two public cases are enough to send a message, especially to people without European citizenship.

You can also see the effect when you look at how the size of demonstrations has changed over the past year. The mechanisms of fear have worked. And it’s not just about threats, it’s also the legal ambiguity. People don’t know what they’re allowed to say or do around Palestine anymore. That uncertainty is part of the repression strategy. Even when courts rule in someone’s favour, like in the Berlin Four case, the damage is already done.

Sophia: Yes, and I think the Berlin Four case is also a good example of how what’s considered “shocking” is changing. One potential effect of a case like this is that it contributes to normalizing the deportation of people who aren’t EU or US citizens. People were shocked that EU or US citizens might be deported but there’s much less outrage about, say, the deportation of Gazans to Greece. That kind of selective response risks legitimizing racialised state violence. And that’s really the danger with how this repression expands, it changes what gets seen as normal, and what gets quietly accepted.

Some people also reacted as if Germany is simply adopting US-style repression. But that’s misleading, repression in Germany has its own logic. The state normalizes it by invoking mantras like “reason of state,” and that framing lets almost anything become acceptable.

But I don’t think we should assume people are just passively accepting this repression. Many aren’t. People are resisting. They’re refusing to be intimidated and that’s important to say too.

Are certain types of repression harder to document than others?

Layla: Yes. What’s especially difficult to document and verify is repression that happens inside institutions or companies, what we call internal sanctions in the workplace. These usually don’t rely on the classic allegations like antisemitism or support for terrorism. Instead, they use more subtle justifications, like saying an event about Palestine is “too political” for the institution, even if it’s taking place on a political science campus, or claiming it’s not “neutral” enough to be allowed.

To prove discrimination, we’d have to show that these house rules are applied inconsistently. For example, discussions on Russia and Ukraine are allowed without similar scrutiny but we don’t systematically monitor other events, and that kind of comparative tracking is often outside the scope of our research. So it becomes much harder to verify that the event was shut down because of its focus on Palestine.

In the Index, you describe how state and non-state actors align organically to suppress dissent. Can you give examples of how that plays out in practice?

Layla: Yeah, I think the most visible example is the media. They often do the initial stage work for something to be criminalized. So you will rarely see anyone being criminalized, or any group being banned, or any demonstration being banned without the work of the media weeks ahead, setting the narrative and manufacturing the consent for the acceptance of that ban and repression that will then come at a later stage.

The media sets up the public to accept what comes next. You also see it in event cancellations. A pro-Israel organization might send a letter to a university that’s already approved an event, and then suddenly the university retracts its decision and cancels it. In that moment, the institution becomes an enabling actor in the repression.

Sophia: One really strong example is with larger events like The Palestine Congress. There were smear campaigns ahead of the event targeting both speakers and organizers, which led to some of the organizers having their bank accounts shut down. So basically, private banks followed media pressure, which then escalated to police presence on the ground.

At the same time, there were restrictions on freedom of movement. Some participants received Schengen-wide visa bans, like Dr. Ghassan Abu-Sittah, who only became aware of it when he tried to enter France. And then the venue itself pulled back. Before the event began, they suddenly raised safety concerns and reduced the allowed capacity. So all these kinds of things come together, and that’s what we mean when we say they work organically, because they all coincide in these ways.

So it’s like a domino effect? Where actions from one sector, like the media or a university, trigger others to respond with their own forms of repression?

Layla: It’s something we try to find evidence for but it’s really hard. And it actually connects to your earlier question about what kinds of repression are hardest to document. We know there are internal letters being sent but we often don’t know by whom, or when, or why they’re being used at that moment.

So we’ll have a case where an institution expels someone or launches an investigation, but we don’t get access to the original letter that triggered it. Where it’s more obvious is in immigration office interviews, especially for people without German citizenship. They’re often asked directly about their political contacts or whether they attended specific demonstrations. That means someone is providing information ahead of time, before a visa renewal appointment.

So we have a lot of hints that there are letters and information being collected about individuals and then sent to their workplace. But it’s difficult for us to document where they come from exactly and who is behind it.

Sophia: But sometimes it is clearer. For example, there are documented cases where events were cancelled after pressure from local antisemitism commissioners. One well-known case is when Achille Mbembe was disinvited from speaking at the Ruhrtriennale.

First, a very well-known conservative blog called Ruhrbarone published allegations about him. Then a local FDP politician, Lorenz Deutsch, who was also the regional antisemitism commissioner — picked it up and started putting pressure on the organizers. After that, Felix Klein, the federal antisemitism commissioner, joined in. And of course, the media amplified it.

You can also see this on a legal level. For example, pro-Israel think tanks like the Tikvah Institute organized an event series last year on expanding criminal law to counter antisemitism. They specifically invited members of the Berlin police and state prosecution office. So sometimes you can trace this coordination very clearly, not just informally but institutionally.

Layla: Another example is the ongoing exclusion of the Nakba exhibition from the evangelical Kirchentag program. It had been included every year since around 2008. But then in 2013, the German-Israeli Society published a brochure claiming that speaking about the Nakba is antisemitic, among other things. Years later, you see the antisemitism commissioner targeting the exact same exhibition, using very similar language, sometimes even the exact same sentences from that brochure. It’s not always explicitly cited, but you can tell where it’s coming from.

Sophia: And that’s what we’re trying to show through the Index of Repression. We have many individual incidents, but for some we go deeper and we feature them to show how different layers of repression unfold: who said what, when it was picked up, how it escalated, and what consequences followed.

Part two of this article will be published on theleftberlin.com soon