Western countries are finally recognizing Palestine as a state, but this overdue gesture falls short in two ways. It is too little, because Palestine has long met the criteria of statehood under international law. And it is too late, because decades of political hesitation—coupled with Israel’s relentless expansion of illegal settlements—have eroded the very possibility of a viable Palestinian state.

Too little: Palestine is already a state

International law has long provided the criteria for statehood. The Montevideo Convention of 1933 requires a defined territory, a permanent population, a government, and the capacity for international relations. Palestine meets them all.

There is a permanent population of millions. There is a defined territory—even if its borders have been repeatedly violated since 1967, when Israel occupied the West Bank and Gaza. There is a governing authority in Ramallah, with legislative, executive, and judicial organs, however constrained. And there is no denying the capacity to establish relations with other states: Palestine has been recognized by more than 150 UN member states and admitted as a non-member observer at the United Nations in 2012. The usual objection is that Palestine lacks “effective control” of its territory, but that is a consequence of occupation, not a disqualification from sovereignty. International law is explicit: occupation does not erase a state, it only suspends its ability to exercise authority. If it were otherwise, Kuwait would have ceased to exist when Iraq invaded in 1990, or France during Nazi occupation.

The international community has long recognized this reality in principle, but has failed in practice. In 1947, the UN Partition Plan (Resolution 181) explicitly envisaged two states which, as reaffirmed in numerous resolutions since, should exist “side by side”. It was never implemented, as intercommunal tensions in Mandatory Palestine escalated into open war between Arab and Jewish forces. The newborn State of Israel emerged from this conflict, while the Palestinian territories of Gaza and the West Bank came under Egyptian and Jordanian control, respectively. Over the decades, the Palestinian state was further smothered in its cradle, even as UN resolutions continued to accumulate. The General Assembly recognized the Palestinian people’s inalienable right to self-determination in the 1970s, and in 2012, Resolution 67/19 conferred non-member observer state status to Palestine. In other words: Palestine is a state by law and by fact. What international law has confirmed, politics has long denied, and that denial has carried a devastating cost.

Too late: the West looked away while the land was taken

For decades, Western governments declared support for a “two-state solution” while privileging their economic and diplomatic relations with Israel. During this time, Israel entrenched what it called “facts on the ground”, such as settlements, roads, and infrastructure deliberately built to reshape the territory and foreclose Palestinian sovereignty.

Settlements in the West Bank, deemed illegal under the Fourth Geneva Convention, now number in the hundreds. According to the United Nations, in 2024 there were approximately 700,000 Israeli settlers living in the West Bank (including East Jerusalem), spread across about 350 settlements.

Moreover, in 2002 Israel began building a separation wall. While justified by Israeli authorities as a security measure, large portions of this barrier cut deep into land internationally recognized as Palestinian, annexing farmland, separating villages from schools and medical facilities, and undermining contiguous Palestinian territorial integrity. In 2004, the International Court of Justice in its advisory opinion declared that the parts of the Wall passing through occupied territory are illegal under international law because they violate, among other norms, the rights of property, freedom of movement, and the right to self-determination.

And now comes the E1 project: 3,400 to 3,500 housing units east of Jerusalem, designed to link the settlement of Ma’ale Adumim to the capital. This corridor would cut the West Bank in two, severing Ramallah from Bethlehem, making territorial contiguity geographically impossible and a Palestinian state less viable. These measures have not only fragmented Palestinian land, but also fractured the daily lives of its people—restricting movement, trade, and access to basic services. Israel’s Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich has been explicit about its purpose: the plan, he declared, will “bury the idea of a Palestinian state”.

The project does not stand in isolation. It reflects a long-standing political vision. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who has repeatedly framed the West Bank as the ancestral land of the Jewish people, has declared at Ma’ale Adumim that “there will be no Palestinian state” because “this place belongs to us”. Such statements underscore that the settlement enterprise is not an accident of policy but a deliberate strategy to ensure that recognition of Palestinian statehood—whenever it comes—arrives too late to matter on the ground.

The West’s partial, and conditional, recognition, does not erase the decades when such statements went unchallenged and when settlement expansion proceeded unchecked. Words now cannot reclaim the territory that bulldozers and concrete walls have already reshaped.

The cost of delay

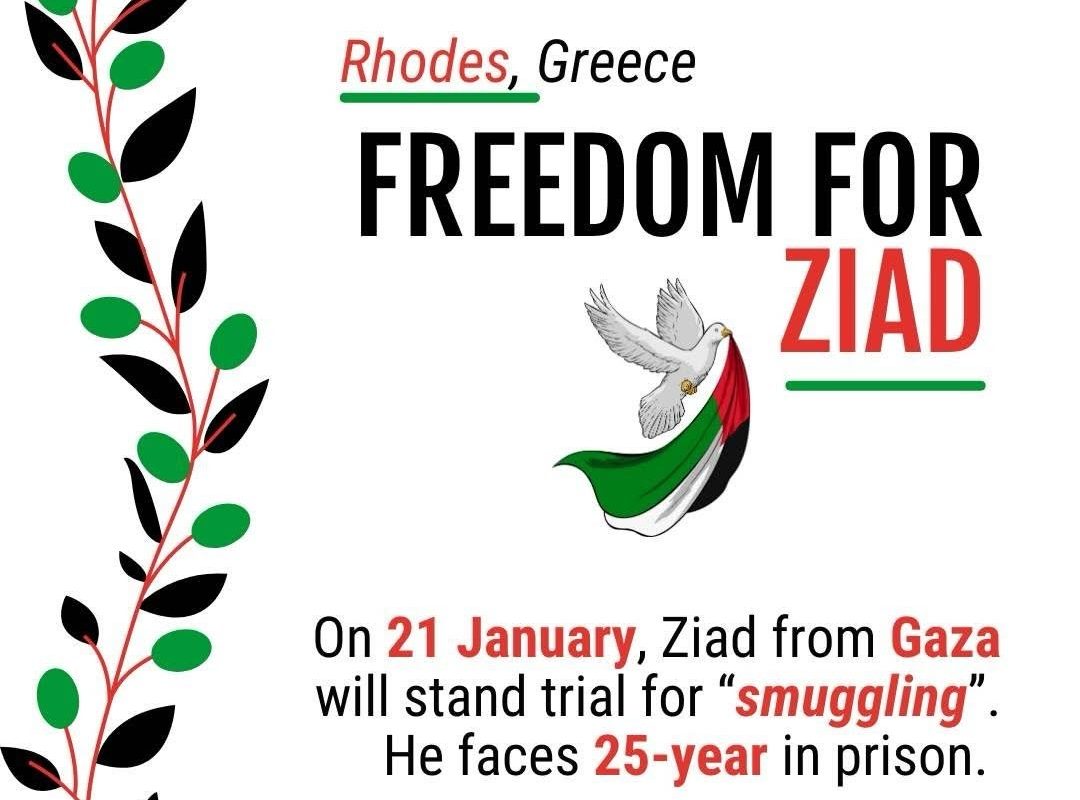

This hesitation has had two devastating consequences. First, for Palestinians, it has meant the steady erosion of their land and rights. Every new settlement, every demolished home, every olive grove seized has made statehood less feasible. In the West Bank, land is carved away settlement by settlement; in Gaza, life itself is starved out. Both dynamics serve the same purpose: to ensure that Palestinian sovereignty remains a right on paper but impossible in practice.

Second, the delay has corroded the authority of international law itself. If clear rules—against annexation, against settlement, against occupation—can be ignored for decades, then what remains of the global order? If law cannot defend Palestine, how can it defend Ukraine against Russian aggression or the Philippines against maritime encroachment? Selective enforcement makes law indistinguishable from politics.

The zebra in the room

For now, Palestine remains the zebra in the room—obvious to anyone who looks, yet officially unacknowledged. It was Benjamin Netanyahu, then opposition leader, admitting it more than three decades ago: “When you walk into the zoo and see an animal that looks like a horse and has black and white stripes, you do not need a sign to tell you this is a zebra. It is a zebra. When you read this agreement, even if the words a Palestinian state are not mentioned there, you do not need a sign; this is a Palestinian state.” The zebra is still there. What has changed is that the cage has grown tighter, and the stripes are harder to see under layers of concrete and barbed wire.

Recognition today is not meaningless. Symbols matter, and Palestinians deserve the validation of their rights. But it is also insufficient. Recognition risks becoming a symbol of the West’s guilty conscience—a gesture too little, too late, for a people whose statehood exists in law but is vanishing. Unless it is given substance, recognition will remain only another entry in the long catalogue of promises to the Palestinian people that history has left unfulfilled.