I was astonished to learn that my first contribution to The Left Berlin was in fact a snap analysis of the previous Norwegian parliamentary election in 2021. Things have come full circle, and I now contribute this preview to the upcoming election in September 2025, writing from Oslo, posing as a foreign affairs correspondent.

First and foremost, it is perhaps useful to justify why the election of a somewhat obscure country of a mere 5 million people is of interest. My primary justification is that Norway is a limit case of progress under capitalism in the 21st century. The Norwegian and Swedish electorates can be considered, within a liberal capitalist framework, to be the most left-wing among advanced economies today (as this Financial Times data journalism story illustrates). A success for the left in Norway is therefore a sign of hope and an opportunity for learning, with defeat being a bellwether of global regression.

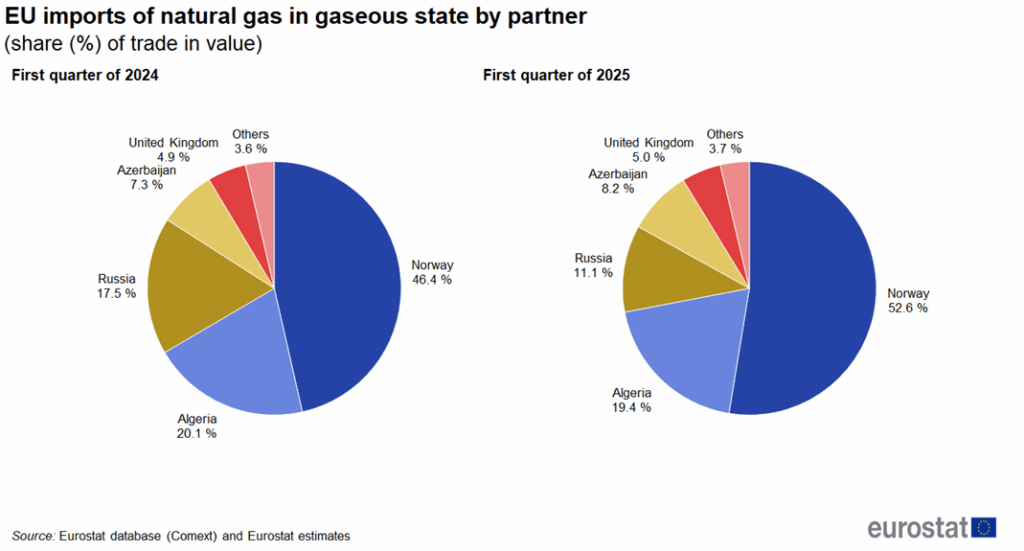

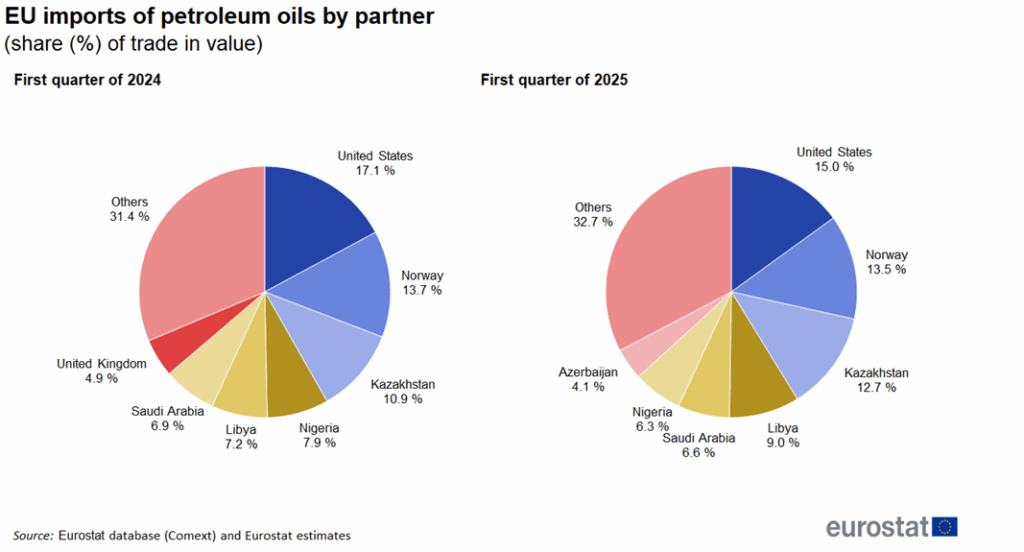

But there are strong economic factors to consider as well. The chief among them is Norway’s role as the largest producer of oil and gas in Western Europe—a sort of Saudi Arabia of Europe on account of being both a petrostate and a monarchy. The EU is particularly reliant on Norway for meeting its energy needs now that Russia is out of the picture as a key supplier, as shown by the figures below.

Source: Eurostat. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

Source: Eurostat. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

Furthermore, Norway has a sovereign wealth fund that owns a whopping 1.5% of all listed shares in the world. This is over 20 times Norway’s share of the global population. This figure of 1.5% is not a trifle, and the choices this fund makes can have a ripple effect on other significant market actors. The figure also doesn’t represent all the financial assets the fund controls; it is merely the headline figure. (I encourage readers to learn a bit more here.) In short, you may not be interested in Norway, but Norway is interested in you.

Setting the political scene

Four years ago, the kingmaker was the Centre Party (Sp), achieving a stunning success that propelled it to the forefront of government with 13.6% of the vote. They ran on a platform emphasising local government autonomy, fiscal discipline, advocating for the interests of farmers, and prioritising Norway over its relationship with Europe.

I predicted that this victory would prove pyrrhic. It did. Current polling predicts Sp suffering a total collapse in comparison to the previous election (see the polling comparison at NRK.no). Despite Sp getting their wish to be part of a two-party minority coalition with confidence arrangements with the Socialist Left Party (SV) and control of the finance ministry, the coalition collapsed in January of this year over Sp’s refusal to implement an EU directive on electricity markets in the EU and EEA that would have raised prices for Norwegian consumers.

Unlike in Germany, Norway has fixed-term parliaments, and early elections cannot be called. The Prime Minister, Jonas Gahr Støre, would have to limp on. The government was immensely unpopular in the lead-up to the split, with a poll in December putting the ruling Labour Party (Ap) at a catastrophic 16.8% (NRK poll), which, if realised, would be the party’s worst vote share since their first parliamentary election in 1906. Furthermore, the far-right Progress Party (FrP) has usurped the Conservative Party (H) as the flag-bearer for the so-called bourgeois (borgerlig) parties. Their extremist leader, Sylvi Listhaug, was in prime position to become the next prime minister. So how, within the space of eight months, has the man that I described to be dull as dishwater managed to turn this hopeless situation around?

Return of the king

Enter stage right: Jens Stoltenberg. Fresh from his tenure as the second-longest serving secretary general of NATO and the most significant Norwegian politician since perhaps the father of the nation Einar Gerhardsen himself, the former two-term Prime Minister and predecessor as party leader was appointed by Støre to the finance ministry, replacing the embittered Trygve Slagsvold Vedum. At a stroke, as if by the aid of Faust himself, polling improved dramatically. Ap went up to 20.2% in January and then 28.7% in February before settling around the 30% mark now. More significantly, this expansion in support for Ap came directly at the expense of the major parties of the right and centre. In a moment of crisis, Støre ran to daddy and daddy delivered. It is now Støre’s election to lose.

Norwegian commentators are utterly mesmerised, struggling to explain how this reversal has come about. They make vague allusions about Stoltenberg’s reassuring qualities vitalising the animated corpse of Ap. Meanwhile, to a Norway observer looking in from the outside, it’s rather sheepishly simple to explain. It’s the Orange Man stupid.

The counterfactual to assess is: would Støre’s party have experienced a revival of some sort on its own as the carnage unleashed by Donald Trump on the world became more pronounced? It’s a coin toss; I would hazard to say yes, but not enough to win an election. The truth is that Norwegian voters were being offered three bad choices for leadership, and now they have one tolerable option on the table, namely a fusion between Støre and Stoltenberg. In an unstable international order, a country whose national self-conception is one of being an insecure upstart will seek to rally around something that promises to help them weather the storm.

Source: Ali Khan.

Ap is the natural party of government in Norway, and Stoltenberg is its most decorated politician of the century. In a world beset by crises, he and his name are a constant in Norwegian public life. (His sister led the Norwegian public health institute during the pandemic and became a regular face on the TV). For a country that feels insignificant, he is the only person of international significance it can lay claim to. The timing of his entry into government was indeed brilliant and Støre should thank Vedum for having left in a huff. Trump’s tariff wars and mania have poisoned any political party or leader who is seen as vaguely aligned with him. For Norway, bordering Russia and a founding member of NATO, Ukraine is an especially pertinent theme, but so is Palestine.

Trump is seen as an enemy of Ukraine, a friend of Putin and Netanyahu, and therefore, his brand is toxic for Norwegian politicians. No party has a stronger association in Norway with Trump and the Republicans than FrP. The rise of the FrP to pole position on the right has ironically strengthened Ap—centrist voters from H and Sp have likely migrated to Ap, reducing the former two to their core rumps of supporters. The rise of the far-right in Norway, troubling as it is, has helped consolidate the left bloc.

The collapse of the centre-right

In all this fanfare about Stoltenberg, it is easy to overlook that he was in fact defeated by a right-wing coalition of H and FrP, led respectively by Erna Solberg and Siv Jensen. This same coalition defeated Støre in 2017. It is not enough to say that FrP is toxic—Siv Jensen oversaw a great moderation in her party that made it palatable— is it enough to say that Erna Solberg, a two-term PM herself, does not represent reassurance. Events have conspired to make things the way they are.

Erna Solberg is a compromised candidate. She was embroiled in a corruption scandal involving her husband making trades on the stock market based on privileged information gleaned from his wife. Solberg somehow survived this scandal as opposition leader by claiming to be a victim of sexism being made to pay for the sins of her spouse. She managed to survive the storm but has been plagued ever since by the stench of corruption. It is a nice testament to the standards of public life in Norway.

The third candidate for prime minister is odiousness personified. Sylvi Listhaug (FrP) had to resign as justice minister for a Facebook post claiming that the Labour party cared more about the rights of terrorists than the nation’s security. She voted against gay marriage before changing her tune to go with the times. She supports moving the Norwegian embassy to Jerusalem and is the staunchest pro-Israeli politician in frontline Norwegian politics. As early as January 2024, 47% of Norwegians supported a boycott of Israel, a number that surely must have skyrocketed by now. Though she claims to be against Donald Trump, describing herself as a Reaganite, she is firmly aligned with the European far-right, having vocally supported the Sweden Democrats (a party with neo-Nazi roots), and the convicted Danish Social Democrat immigration minister who was found guilty of violating the rights of Syrian refugees. She has led her party to the forefront of the Norwegian right, received millions of kroner in financial support from the private sector and their front groups, but her support has a ceiling due to her reputation as a polarising figure.

The story on the margins

Unlike the previous election, which saw significant movements on the margins of Norwegian politics, this election is relatively subdued. Minor parties have long played a decisive role as their ability to get at least 4% of the vote can determine the colour of government (red or blue). Sp ensured that the far-left could be shut out of any decision-making last time, but, should polls bear out, Sp would be leapfrogged by the very party they sought to act as a guardrail against—delicious schadenfreude.

Where previously it was a tremendous breakthrough to go from 2.4% to 4.7% between elections, this time the far-left Red Party (R) might expect a modest 1% increase in support and gain one extra member in parliament. The other left party, SV, is practically fossilised around 8%, statistically tied to its previous result despite fresh leadership. Disappointing. It is a tug of war between these two parties to claim supremacy over the mantle of left-wing opposition to Ap, despite there being little to distinguish the two parties. R is a more Eurosceptic, left-purist party, while SV has been carrying the banner for socialism much longer, and their ideological purity has been diluted over time due to the hard business of negotiating with power.

The biggest change on the margins is the fate of the Green Party (MdG), which narrowly failed to cross 4% last time but has since receded to under 3%. They are now irrelevant. Their singular focus on environmentalism has left them crowded out. They are a retail politics party, and not a lot of people are buying their organic produce. The Bible bashers at the Christian Democratic Party (KrF) are doing one big heave to break past 4%, having slipped under last time. If they do, that would ironically shift the parliamentary arithmetic in favour of the radical left parties. The weird eco-market liberals at the Liberal Party (V), the closest parallel to Germany’s FDP, are hovering steadily above 4%. Should they go under it would help Støre, since H and FrP would have no coalition partners to speak of—another sign that fate has conspired against the right for once.

FrP and H have run a boring, old anti-tax, pro-business, red-scare election campaign, conjuring apocalyptic visions for the Norwegian economy should a Støre government have to rely on the Marxists to have a majority. The wealth tax instituted by Ap has been their biggest bone of contention, and they are raising the spectre of tax increases should R have any say on policy. Once again, it is ironic that should Norwegian voters want to avoid this situation, their best chance lies not in supporting the right but rather defecting to Ap, such that a majority without R would be possible. They’re cooked as Gen Z might say. The right only has itself to blame for its woeful unpreparedness for the world-historic juncture at which Norway finds itself.

Conclusions

The centre-right gambled on trusting Solberg to lead them, and the gamble failed. The far-right gambled on leaning on its inherent extremism and succeeded a little too much, alienating the otherwise moderate Norwegian electorate that spends a little bit more time touching grass than being driven to extremism on Facebook than its peers in Europe. All the left bloc had to do was not interrupt their opponents while they made their mistakes and let world history push them over the edge.

Frankly, Listhaug is an evil woman, a blight on humanity. Her only chance of success lies in somehow detoxifying herself along the lines of Georgia Meloni in Italy. She has undergone something of a makeover in the lead-up to the election, while still hoping to draw attention away from herself as a potential PM, even though she is now clearly the main alternative to Støre. The state broadcaster still frames it as a contest between Støre and Solberg—a complete mystery—but he is seen as the preferred PM candidate to Solberg by a margin of 10% in polling. Compared to Listhaug, the numbers would be even worse, and Listhaug would probably be glad if nobody even frames that question. She’s a burglar hired by private firms and lobbyists for Israel trying to get into the PM’s office through chicanery and deceit. It would be a tragedy if she won somehow, but, as things stand, it is very unlikely. On the other hand, the radical left should consider it a success if it holds its position in conditions where other radical alternatives tend to get their lunch eaten.