Over the last few years the German state has increased its levels of repression towards any form of Palestinian solidarity, as well as a disproportionate increase of targeting of Arabic and Muslim voices and persons. The police act with impunity in their arbitrary violence and scant regard for constitutional laws, often clashing with the high court’s ruling, yet facing zero consequences or accountability for their law breaking. The hostile and often false narratives of political leaders and the complicit media class create a falsified legitimacy for the draconian policing of those supporting Palestine, with ever increasing “new normal” levels of violence becoming established.

If we examine the European convention of human rights, articles: 8 (Right to Privacy), 10 (Freedom of Expression), and 11 (Freedom of Assembly & Association) are being ignored on a daily basis here in Germany. In early May 2024, the ELSC (European Legal Support Center), presented the first comprehensive Database of anti Palestinian repression in Europe. 2032 (recorded) incidents occurred between 2019 to 2025, of which 736 took place in Germany alone, with nearly half of those transpired in Berlin. Such serious breaches of European law occurred that the Council of Europe’s Commissioner for Human Rights, Michael O’Flaherty, expressed his concern directly to German Interior Minister, Alexander Dobrindt, about the (lack of) Freedom of Expression and Freedom of Peaceful Assembly over protests related to Gaza in Germany.

O’Flaherty noted restrictions on events, symbols, or other forms of expression in this context in Germany, also citing reports of the police using excessive force against demonstrators, including minors.

Berlin has almost twice as many police officers as other EU and German cities, totalling 500-594 officers per 100,000. All the while Germany extols its virtues of being a progressive nation, yet in actuality operates as a state in which a highly militarised and violent police force faces zero accountability for injuring & brutalising its population, whilst disregarding constitutional fundamentals such as right to protest and freedom of opinion, often in the name of freedom of opinion.

One comrade recounts:

“After a demo in October I ended up being checked for internal bleeding and organ damage in hospital, after being beaten by multiple police simultaneously. They had started their attacks in the crowd, and I rushed to help someone I saw being kicked on the floor. I was attacked by multiple police officers, my arms were held by two, each using their free hands to punch my ribs, chest, and stomach repeatedly, whilst another held my head back in a pain grip, meaning I couldn’t physically move whilst getting beaten. I was detained, put in a van, and driven to a police station in Potsdam, where we were made to wait outside in the cold winter weather for about 30 minutes, until being processed and released, with no charges. My body was still in so much pain the next day that I went to hospital, where they examined me for organ damage and internal bleeding, using the CT scan, and I proceeded to fall into a state of shock, lasting several hours.

I have since recently returned to a hospital ward post police treatment, after a demo at Checkpoint Charlie, where I was punched several times in the neck and face by one policeman, 34311, smashing my glasses into my eyebrow, requiring stitches, and leaving me with migraines for several days. This same policeman, number 34311, is being charged by a group of lawyers called Advocardo, who specifically target police who do the most damage. They asked me to be a witness in that case, after seeing the video of this attack online.”

This is but one of many examples of the extent of violence, as well as the tactics employed: the “pain grip”, targeted pressuring of sensitive body parts to gain compliance, is directly learnt from the IDF, taught to police and militaries worldwide for extreme crowd control, the distressing result of which is that the restricted airways lead to the victim being rendered completely prone and vulnerable, easily led and subsequently beaten, without any opportunity for bracing for the assault, leading to increased damage inflicted.

These accounts will be portrayed by the German media as violence toward police, so registered by the police themselves, when it is the complete opposite. Even demonstrators who get carried away are recorded as perpetrators of violence. For example, the now infamous case of the Nakba stomping: the supposed breaking of one officer’s legs was entirely fabricated, and rejected by the courts upon review of video evidence. Yet the police and media sources who reported the falsehood were not held accountable.

Previous demonstrations impacting far more civil disruption were allowed to play out with minimal police interactions, and certainly no expectation or experience of unwarranted violence. Specifically, during Extinction Rebellion’s early actions, Potsdamer Platz was blocked in entirety from five a.m. to nine p.m., ending when Police (none in riot gear), peacefully removed protestors away into vans for processing. Years later, they escalated the repression of climate protests after it seemed the state became embarrassed by the lack of control over its infrastructure, leading to some scandal in the mainstream media at the heavy handed tactics, seemingly as it was imagery of white Germans being persecuted.

It is now guaranteed that at any given Palestinian demo, Police are dressed to oppress: full helmets, riot gear, and often sporting specific “self defence gloves” (sand filled for further damage inflicted, courts finding that use of these in extreme beatings could be considered attempted murder). At no point during any protest does it feel the police are there for anything but violence; they project their monopoly of it from the beginning, until enacting it after orders allow them to do so. They are the escalators, they are the instigators, they are the gatekeepers of violence, and everyone knows it.

Another comrade recounts :

“At the IQP (International Queer Pride), 2024, I was attacked from behind by the police and detained and booked, not formally arrested. I had to be taken to the hospital by ambulance afterwards, my most major injuries were two cracked kneecaps, a deep laceration on my arm that required stitches, and an almost broken arm that I had to keep in a cast for two weeks.

I still did not receive any charges a year later, so nothing to legally connect and report the attack by the police. “

Longer term realities of expressing opposition to genocide accrue state violence of different kinds, including but not limited to: job and home raids, deportations, targeted detainment and harassment, and online and infiltrating surveillance. One example was two Girls and Young Women shelters in Berlin being shut down, due to “hatred of Israel and antisemitism “. In actuality, staff members marched in support of Palestine, posted “banned” slogans on their private instagram pages, and appeared as speakers at the Palestine Congress, which was banned and shut down by German authorities on the orders of Berlin mayor Kai Wegner, the same man who said, “The Israeli flag will remain hanging on the Red City Hall until the last hostage is free—and nothing will change that”.

With Netanyahu’s current determination to get those hostages killed, it seems Germany is staying with Israel until it sinks into its future international ostracisation and legal prosecutions for the horror it is unleashing.

Giovanni Fassina, Director of the ELSC, noted:

“The audacity with which German authorities bend and undermine the law should not surprise us at this point. However, it remains shameful. We have witnessed this time and time again: German authorities are now routinely making up baseless accusations to justify increasingly harsh measures against the Palestine solidarity movement.

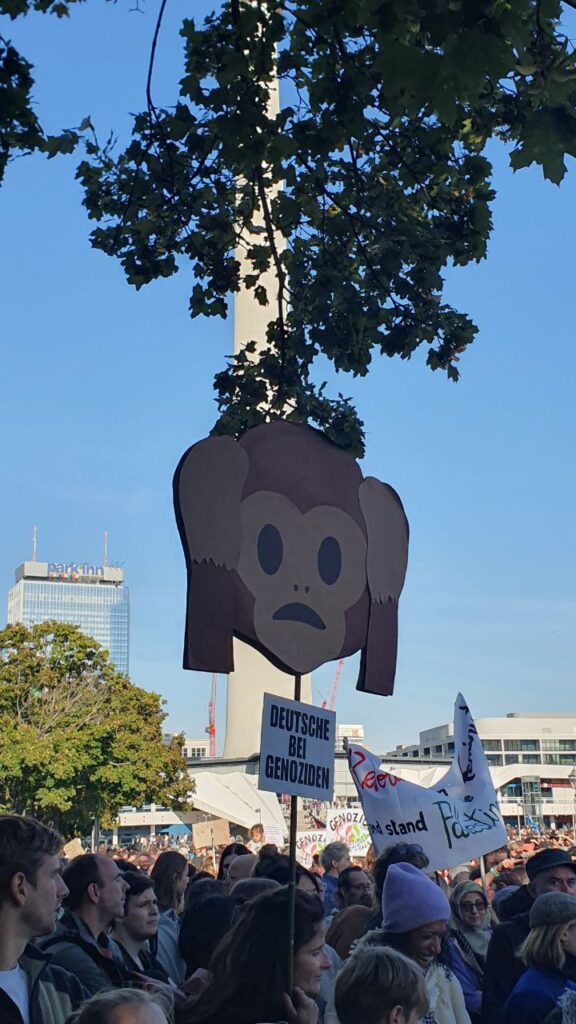

These increases and normalisations of authoritarian behaviour are of grave concern. The recently updated Weapons Act (WaffG) in June 2025 prohibits dangerous weapons being carried in public places, yet it allows the police to detain and search anyone they perceive as a risk. This brings about stop and search tactics, which unsurprisingly mainly affect young men of ethnic minority groups, as we have seen occur in the UK after similar laws were passed years ago. We can safely assume that wearing the Keffiyeh, or having any pro Palestine symbols (the ever dangerous watermelon), will allow the police to apply greater acts of intimidation & repression, they must be held accountable for their barbarism.