161. AFA. anti-fascism.

Nowadays we are on the verge of collapse—collapse of everything we know about political activism, peace, and the seemingly stable system of international relations. We are closer than ever to the moment where new forms of fascism and feudalism will appear and the only way we can prevent this is by moving.

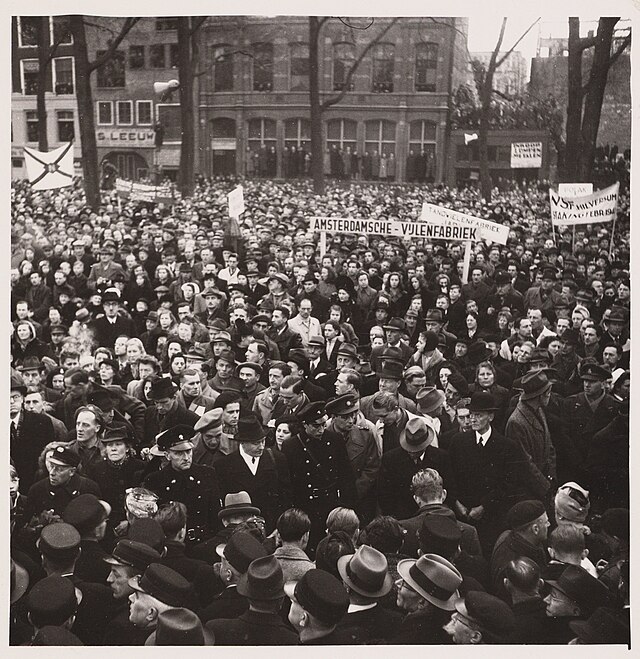

At first it sounds strange but in order to escape the cage of this new-wave, right uprising we have to move towards the revival of Antifa movements around the world and talk about the troubles around such uprisings. The far-right is on the rise and we have to worry about it, because at the same time the left is far from its glory. But what exactly is anti-fascism and how do we understand it?

For some reason or another, it’s not easy to answer this question. To make it easier we have to start from some theory of anti-fascism as a concept. And for that, Simone Weil is a useful starting point. But first, I should offer a brief biographical overview of Weil to better understand her ideas. Weil is a French philosopher, university tutor, revolutionary, Marxist and last but not least, a well-known antifascist, who lived until the early 1940s.

The only great spirit of our time, as Camus called Weil, states that “The relative security we enjoy in this age, thanks to a technology which gives us a measure of control over nature, is more cancelled out by the damages of destruction and massacre in conflicts between groups of men.” This is applicable to our current epoch and is a perfect example for the repetitiveness in human history.

Today we think we govern ourselves, others, and nature justly, but the reality doesn’t show the same. There is a significant alienation from labor, thought, and reason that fuels xenophobia, racism, fascism, and hatred. This alienation is accompanied by an intellectual decadence, which makes this issue even harder to solve. By admitting this, we are forced to confess that we have no other choice—we have to fight.

As Hannah Arendt argues in her concept of the banality of evil, fascism does not always emerge through monstrous figures but through ordinary individuals who stop thinking critically. This transforms anti-fascism into an ethical duty—an active refusal to become passive instruments of oppression.

HOWEVER, anti-fascism is not an absolute solution. It is not a panacea; rather it is more of a proto-concept. It does not give a solution to any of the described difficulties—though it is an exemplary first step, it won’t be enough. And proof for such a controversial statement can be found in Weil’s work. She states that anti-fascism in the popular narrative stands for “anything rather than fascism; anything including fascism, so long as it is labelled communism.” If we need to objectify Weil’s definition, we can illustrate anti-fascism as an ouroboros—a snake eating its own tail.

Herbert Marcus helps us understand this confusion through his idea of “repressive tolerance.” He points out that tolerant societies allow intolerant ideologies to flourish until they destroy democracy from within. anti-fascism thus becomes a protective boundary—a sui generis dedication not to extend tolerance to the utmost.

Fast forward to today we can see that fascism is not dead, it is here, but in new forms. Raging Zionism, neo-fascism, and different far-right ideologies are here to stay.

As Walter Benjamin noted, fascism turns politics into aesthetic spectacle, using symbols, images and myth-making to seduce the masses, to look more attractive to them. Today’s far right weaponizes digital culture and social media the same way. Through performative violence, visual propaganda, and viral narratives. Effective anti-fascism has to therefore dismantle not only the ideology, but also the spectacle that sustains it.

We might say that anti-fascism itself is not the solution in its current form. We have to decide whether or not we want a better future. Fighting for new Antifa movements is the only way we can manage the crisis.

In order to make a difference we have to develop this ornate conception. We have to give it form and content. Trump’s witch hunt against Antifa, the lessons from working and stable antifascist movements such as Greece’s, and, last but not least, rethinking the ideas of political theorists like Emma Goldman, Simone Weil, Gramsci, and Ernest Barker can all serve as catalysts.

Antonio Gramsci in particular provides a pivotal framework. His theory of “cultural hegemony” reveals that fascism thrives when dominant groups shape the norms of society. Fascism becomes possible when cultural and intellectual spaces surrender. anti-fascism must operate not only in the streets, but in classrooms, media, literature, and collective imagination. It must build counter-hegemony—alternative structures of meaning that are based on solidarity, equality, and critical thought. This involves creating institutions, networks, and cultural practices that challenge the ideological rise of this neo-fascist wave. Without this cultural struggle, political resistance will always be incomplete.

Jean-Paul Sartre deepens this by reminding us that in moments of moral crisis refusing to act is itself a choice, a choice that supports the oppressor. Anti-fascism therefore, I think, becomes a form of responsibility; a form of commitment.

Only through continuing the fight can we keep ourselves, our societies, and our rights. We fight; therefore we are. Conceptualize, create, unite.